ABSTRACT

This formative evaluation examines the process of curricular change as a College of Osteopathic Medicine develops a competency-based curriculum. The study explores how faculty perceive the need for change, the process of change, and the results of specific changes to guide the college in the change process and improve the chances of achieving a long-lasting and well-accepted curriculum innovation. Study objectives were to determine status of faculty members regarding: a) levels of readiness for change early in the change process, including changes in perceptions after implementation; and b) specific concerns and level of use of the Competency-Based Curriculum. The evaluation is based on well-established principles that focus on change, first in individuals and then in organizations. The Concerns-Based Adoption Model describes seven levels of concern that users experience while adopting a new program or practice. The Stages of Concern (SoC) questionnaire was administered to all basic science and clinical faculty, and to related staff. The results showed an overall profile consistent with an institution beginning a change process. The profile revealed very high awareness concerns, moderately high information and personal concerns, moderate concerns in management, low concerns in impact or consequences, with rising concerns in collaboration and refocusing. The institutional profile shows the typical non-user profile except for some tailing up at Stages 6 and 7, which may indicate resistance to the innovations. Understanding the profile will help in tailoring information and training sessions. Follow-up interviews of a purposeful sample of faculty focused on the five key elements of the Competency-Based Curriculum: overall integration of national competencies; student accountability for learning outcomes; curriculum scope based on clinical relevance; innovative use of curriculum time and instructional modalities, and curriculum expansion allowing student choice. Interviews were analyzed for level of use and stage of concern, bringing to light new themes that will guide faculty development and implementation.

INTRODUCTION

When the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) set new standards for competency-based curriculum during residency education in the United States, many medical schools replicated the process in an effort to establish a pre-doctoral education foundation for the new core competencies. One medical school organized a committee of 22 faculty and staff to review the current curriculum and implement the competency-based approach to curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Dialogue within the curriculum committee resulted in the identification of five elements as guiding principles for the design of the curriculum:

- Integration of national core competencies

- Curriculum scope based on clinical criteria of commonality and criticality

- Student responsibility for course learning outcomes

- Innovative use of curricular time and instructional modalities

- Student opportunity, flexibility and choice toward professional growth

A focus on national competencies and course learning outcomes as components of the medical college curriculum was a major step in moving to a competency-based educational approach. This represented a significant paradigm shift to move the institution into harmony with a growing and worldwide emphasis on the use of learning outcomes and competencies for the education of all health care professionals. Each discipline and academic subject contributes its own set of outcomes toward the education of the total physician; therefore, the faculty of each discipline/academic subject need to examine their concepts, generalizations, rules, principles, skills and attitudes to reflect a longer-term concern for development of abilities such as research and learning strategies, critical thinking and communication. In directing attention to how students will ultimately apply the knowledge and abilities they acquire, this approach required our medical educators to look beyond the strict boundaries of disciplinary tradition and demands.

The committee leadership wanted to know if the current faculty and staff perceived the need for change, understood the procedures for change, and were aware of specific decisions that were guiding the college toward a new curriculum. A group of medical educators was charged with conducting formative evaluation of the development process itself. By focusing attention on the process of curriculum change, we hoped to improve the chances that a successful curriculum innovation would be both well accepted and long lasting.

This article presents the first stage of a formative evaluation of one institution’s curriculum development process and its impact on faculty, students, and the college. This evaluation was based on the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) developed from a set of principles of change described by Hall and Hord1, which have become part of the established language of change theory. These principles are:

- Change is an ongoing process, not a short-term event, and requires ongoing support and resources and it takes time. It is important to have realistic expectations about the time needed to see significant progress.

- Change occurs in individuals first, then in organizations. Curriculum change cannot succeed unless people are ready and willing to implement it. Individual change is difficult if the organization is not supportive of the change

- People go through change at different rates and in different ways. Individual needs for information and training vary greatly.

- As people implement a new program, their concerns change.

- Change agents must adapt to individuals’ changing concerns over time to ensure effective organizational change. Faculty may need opportunities to share their experiences and learn from one another.

- Change agents need to consider the larger system in which a program is being implemented, taking into consideration the impact on other individuals and parts of the program or schedule.

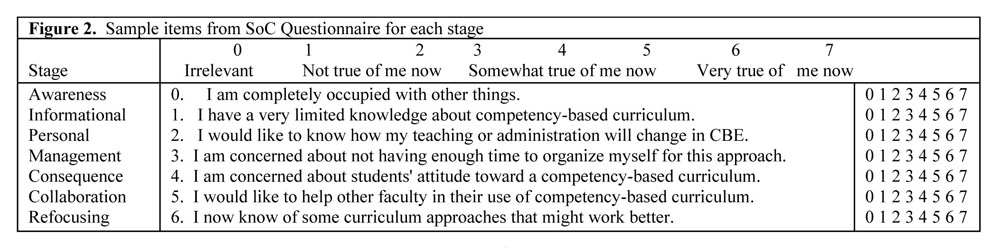

Hall and Loucks2 developed diagnostic instruments and change strategies from these principles. The model combines an examination of stages of concern and levels of use regarding innovations as a framework for planning staff development interventions. Hall and his colleagues3 created the Stages of Concern (SoC) questionnaire to measure the model’s seven levels of concern that users experience when adopting a new program or practice (Figure 1). In reality, everyone involved with a new program has all of these concerns all the time at varying degrees of intensity.2-3 By identifying concerns at a specific point in time, change agents can understand the dynamics of individuals’ perceptions of change.

Use of CBAM has not been reported in the medical education literature on curriculum change; however, the model has been applied successfully in nursing and nursing education research. Lewis and Watson4 used the SoC questionnaire to measure the concerns of 57 nursing faculty about the use of computer technology. Their pre-post study results suggest that the primary concerns of the faculty were informational and that addressing these concerns through workshops increased interest in the innovation. The study showed that the SoC questionnaire was a useful tool to monitor and manage the process of change. The SoC questionnaire was used by Gwele5 to measure the concerns of nurse educators (n=93) at four nursing colleges during the implementation of a major legislated curriculum reform. The author concluded that when a staff is required to adopt a major curriculum change the normal progression through the stages of concern is impeded. The study suggested that in these situations it may be important to delay adoption until participants can come to terms with the need to adopt the new curriculum. The SoC instrument was also used in a study to assess the concerns of staff during the installation of a telemedicine system and to assure that concerns were addressed during system implementation. Survey findings were used successfully to modify the implementation and training phases of the program to better meet the needs of the staff.6

These studies show the importance of recognizing individual and institutional concerns during the change process. By gathering data based on a strong conceptual framework for documentation of the change process, medical educators can provide the Curriculum Review Committee and faculty with targeted support as they move toward development and implementation of a new curriculum.

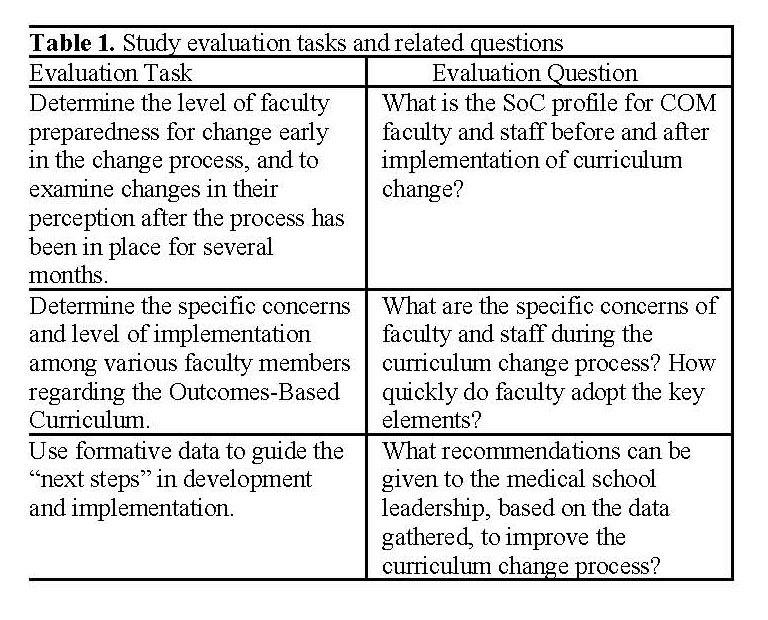

For this study, the evaluators established three implementation goals and corresponding evaluation questions (Table 1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study design utilized qualitative approaches for evaluation of the change process. The Concerns-based Adoption Model was selected because it directly focuses on the implementation of curriculum innovations rather than broad organizational change. In addition, CBAM targets the individual or teacher as the critical unit of change. Importantly, the model provided a validated diagnostic instrument. Data were collected through the Stages of Concern (SoC) questionnaire and personal interviews with identified faculty and staff. The evaluation team included four medical education specialists, one physician, and one basic science faculty member. The study proposal was submitted to the university Institutional Review Board (IRB) and received exemption in March 2005.

The stages of concern among medical education faculty and staff were measured through the self-administered Stages of Concern (SoC) questionnaire designed by Hall and his colleagues.7 The questionnaire, a 35-item rating form, has strong reliability estimates (α= .65 to .86) and internal consistency (α= .64 to .83). The Stages of Concern (SoC) questionnaire was constructed to apply to all educational innovations. Items stay the same with the only change being the insertion of the name of the specific innovation as shown in Figure 2. Each of the seven stages has five items randomly distributed within the questionnaire. “The respondent marks each item on a 0 to 7 Likert scale according to how true it is that the item describes a concern felt by the individual at the present time.”8 The “0” of the scale is recommended for marking items that are completely irrelevant.

Paper copies of the SoC questionnaire were distributed to 60 members of the full-time faculty and relevant staff in May of 2005 along with a brief explanation of the five proposed curriculum elements. The sample was chosen to include all basic science faculty, all clinical chairs, and representative clinical faculty at University Health Care with active roles in teaching at all levels. All staff members with active roles in curriculum implementation were also identified. A follow-up request with the questionnaire attached was sent one month later. A third opportunity to complete the questionnaire was offered to individuals prior to each interview. All three opportunities were given during the summer when classes were not in session and in the early phases of curriculum revision when most of the five curriculum principles had not yet been incorporated into a new curriculum. To assure anonymity, respondents were requested to mail or FAX their completed questionnaires to an Administrative Assistant assigned to the curriculum committee. The Administrative Assistant, working on a password-protected computer, recorded data on a spreadsheet; no identifying data were retained.

Analysis was conducted using a process described by Hall and associates.9 Each stage has five items that can provide a raw score between 0 – 35. Raw scores for each individual’s questionnaire were tabulated; the group mean was computed for each stage of concern and adjusted to percentiles using a conversion table provided in the scoring manual. The percentile for each stage equals the intensity of concern at that stage. The percentiles are presented as an institutional profile and compared to a typical non-user profile for analysis as recommended by Hall and associates for the introductory phase of a curriculum innovation. A graphic representation or profile of the percentile scores was used for interpretation of the SoC data.

In order to gain a better understanding of the faculty concerns, an interview guide was developed to focus attention on each of the stages of concern while allowing for spontaneity during the interview itself, which provided an opportunity for emergent questions flowing from answers within the interview. In addition to taping all interviews, each interviewer also recorded field notes.

Researchers purposely selected 29 faculty and staff because of their potential involvement in the development and implementation of the curriculum. Interviews were completed with 25 faculty and staff; four were excluded due to scheduling conflicts, refusal of interview, or tape malfunction. Interviewees included eight clinicians, thirteen basic scientists, and four administrative/staff personnel. Eight of the interviewees serve on the 22-member Curriculum Review Committee, reflecting a similar distribution of committee members to college faculty and staff. Interview tapes and hand-written notes were transcribed, and names were removed. The transcripts were distributed to the six members of the evaluation team. Interviewers had little previous connection to their interview panel to avoid conflict of interest based on department or work assignments. Each team member coded all interview transcripts individually. Using contextual analysis for coding of responses, several themes emerged for each question that had structural corroboration and referential adequacy.10 Subsequently, team analysis focused on identifying specific concerns of interviewees, level of understanding, and use of the five key curricular elements. These concerns were then linked to the first four stages of the Concerns-Based Adoption Model – Awareness, Informational, Personal, and Management – because the model focuses on early concerns at the beginning of curriculum development. The use of qualitative reflection by the research team during coding revealed additional linkages and relationships.

Limitations of the Study

The curriculum innovation is still at the conceptual level and does not yet contain critical details that require future faculty work. Although the responses to the questionnaire came from only 53% of the faculty/staff, these are primarily full-time employees and are the most active in the process. Because researchers reported the average of the questionnaire for the institution in the profile, individual differences may have been masked.11

Six different interviewers used the protocol, working from varying depths of experience with the curriculum change process, the stages of concern framework, and interviewing skills. One individual refused the interview; two individuals could not be scheduled, and one tape malfunctioned without sufficient backup notes for use. While personal disclosure may be somewhat uncomfortable in the beginning, it is an important and necessary step toward collaboration within the faculty and staff. The researchers maintained confidentiality with regards to the questionnaire results and the corresponding interviews.

RESULTS AND ANALYSES

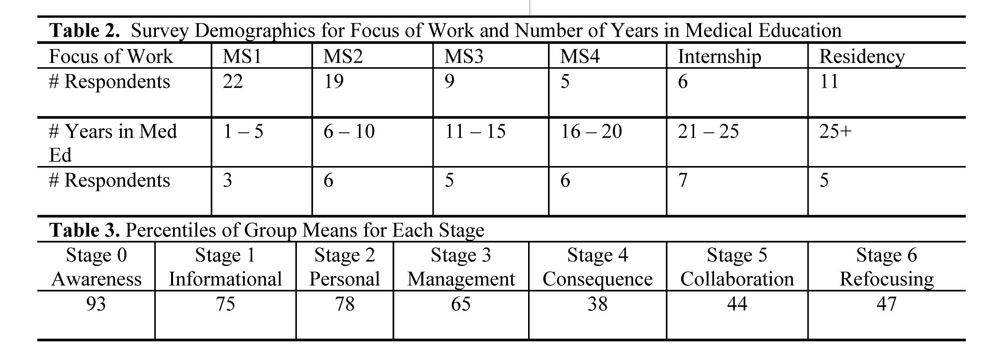

The demographics of the respondents to the survey showed an overall representation of the college personnel. Several respondents did not respond to all demographic items. When examining their role in the college, 26 (81%) respondents were identified as faculty, and six (19%) respondents were identified as staff. Of those identified as faculty, 12 respondents were basic science faculty and 14 were clinical faculty. There was no category for faculty who are medical education specialists, so these individuals were classified as staff if they did not have direct teaching responsibilities. We did not have a demographic choice for Administrators. Most of the respondents focused their educational work at the MS1-2 level or at the graduate level, although many respondents indicated more than one level of primary teaching responsibility (Table 2). The distribution of years in medical education shows a relatively mature college (Table 2).

All analyses were conducted using the instructions from the SoC Questionnaire Manual. The item responses of the SoC questionnaire were tabulated by stage to determine an individual raw score for each stage, and a group mean for each stage was computed. The group mean was assigned a percentile using the SoC conversion chart from the manual and plotted to create a profile (Table 3).

The profile of our institution was analyzed holistically in comparison with a typical non-user profile as shown in Figure 3, since the college is at the beginning stage of curriculum development. When looking at the profile of peaks and valleys, the intensity of each stage is not as important as the relationship between stages. The next step was to analyze the individual stages.

If you place the COM Institutional Profile on top of the Typical Non-User Profile, you can see that these two profiles are essentially congruent. The institutional profile indicates that our faculty and staff are intensely aware (Stage 0) that the development of a competency-based curriculum is underway, but do not have adequate information (Stage 1) about the process and the specific elements. As such, the intensity of personal (Stage 2) and management (Stage 3) concerns has remained high even after a year of deliberation by the Curriculum Review Committee. Consequence (Stage 4) concerns are much lower and in keeping with the typical profile of non-users; however, collaboration (Stage 5) and refocusing (Stage 6) concerns begin to climb again.

Hall and Hord12 suggest that any tailing up of the Stage 6, Refocusing Concerns, on a nonuser profile should be taken as a potential warning that there may be resistance to the innovation. An emphasis on refocusing at this early stage can indicate an attitude of disrespect for the innovation. Coupled with the lack of information apparent in the profile, such a tailing up might also indicate that many faculty members have felt left out of the process. Resistance is also indicated by a high Stage 2 Self Concerns percentile. These may be normal characteristics of persons who are uncertain about what will be expected and may indicate self doubts about one’s ability to succeed in the new program.13 In our institution, the high tailing up at Stage 6 Refocusing may reflect the fact that the specifics of the new program have not been developed, only the principles. Hall and Hord interpreted this profile as a positive, rather than distrustful non-user profile.14 In this evaluation study, the institutional profile was used as a diagnostic tool and established a baseline for further analysis after the curriculum has been fully developed and implementation is under way.

INTERVIEW RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

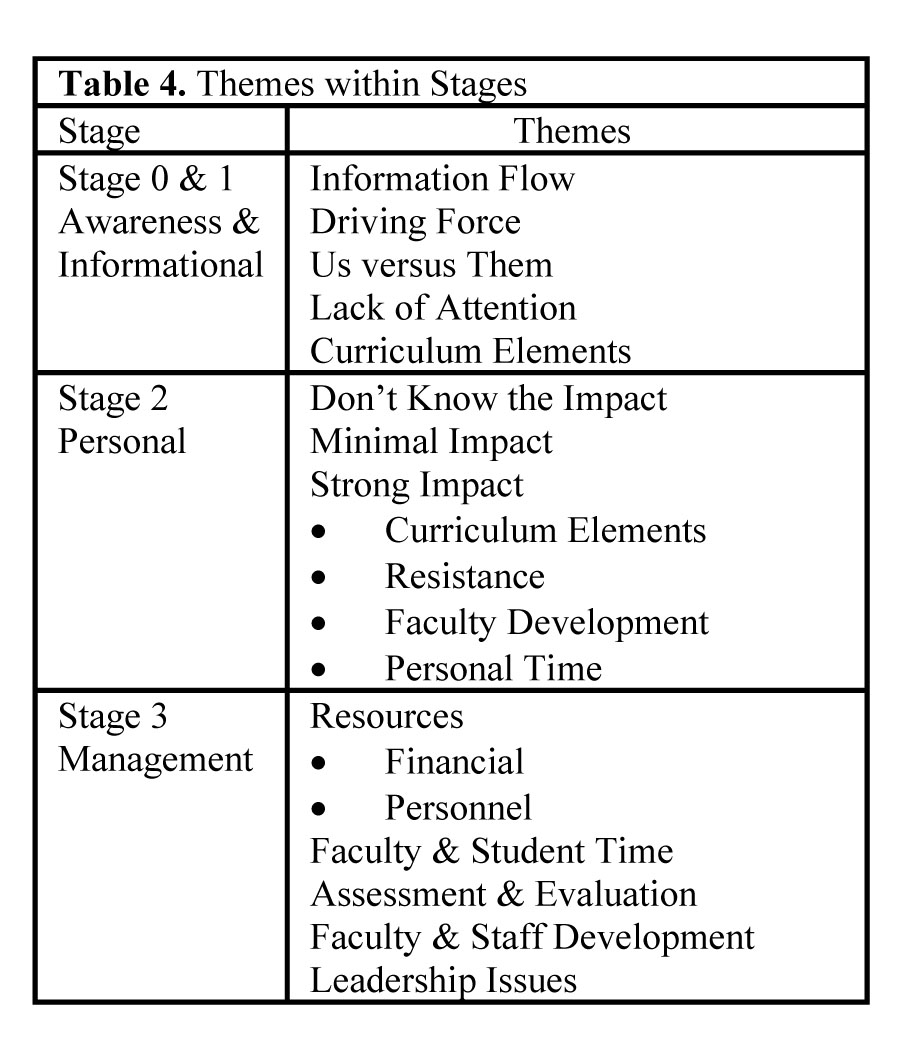

The follow-up interviews were conducted to gain a sense of what was producing this institutional concerns profile. The interview protocol was organized to reflect the first four stages of concern (awareness, information, personal, and management) since the curriculum had not been fully developed at this time. Within the stages, sometimes overlapping themes emerged that will be used to plan change strategies (Table 4). Respondent quotations from the interviews are often used to support and illustrate the findings.

Awareness and Information (Stage 0 & 1)

Interviewees were aware that the College of Osteopathic Medicine had a committee charged with curriculum revisions. They also had some awareness of the new national competencies, but did not know about the set of curriculum elements that had been established by the committee to guide the next phase of curriculum redesign.

Information Flow. A majority of interviewees did not have enough information about the process after one year of deliberation by the Curriculum Review Committee. Most of the faculty and staff who understood the process were on the Curriculum Review Committee. Interviewees felt there was no clear structure or place to get information. Most information on the process came through participation in the Curriculum Review Committee or the Academic Affairs [Curriculum] Committee; the process had not filtered into department meetings with the exception of Pharmacology. Faculty and staff members repeatedly described their basic medium for information flow: informal hallway conversations that may have lacked accuracy.

“People have corridor conversations. We are not trying to second-guess the process.”

“I hear hall talk a little bit, but I would like someone to discuss the overview and where we are going.”

Because of this, clinical departments and individual faculty members who are not on campus have more challenges getting the basic information. One clinician acknowledged the information flow from her participation in a systems course and interactions with the systems manager.

“The curriculum process has been very vague. The process was not spelled out. We need to know the next steps in the process, evaluate it, and discuss it. My faculty members are completely in the dark about the process.”

“Not really enough information, but my systems manager has been very innovative and lets me know what is going on with the process; we are passing ideas back and forth.”

Driving Force. Throughout the interviews, it was apparent that the faculty and staff wanted answers to basic questions such as, who makes decisions in curriculum change? What is the driving force for curriculum change? Three basic scientists voiced the concern of others:

“Usually when something like this is done, it is in response to a concern, so what are the problems? What needs to be fixed?”

“Are we going to just cut hours? What are the criteria for the changes?”

“I’m not too happy about that whole thing [new calendar] in terms of what drives the curriculum.”

Us versus Them. Another basic scientist expressed a positive perspective describing the Curriculum Review Committee as a group of ‘honest, caring, smart people addressing themselves to a problem, which is the same context in which I am working. I trust them to do it.’ However, several respondents used the phrase “Us versus Them” with different meanings — scientist versus clinician, committee member versus non-members, external faculty versus professional educators.

“The way the school is set up, the curriculum process is driven much more by the basic science faculty and outside consultants that may or may not have active clinical practices or may have some clinical role, but are still more [like] professional educators.”

“There is a false tension between basic science and primary care clinicians. We need the best clinical resource: a specialist. We need to phase down Pathology and Radiology since no one looks at slides and images — they go to a specialist.”

“Things have been thrown out of the GI system and shouldn’t have been. ‘They’ often don’t know the framework of the discipline.”

Lack of Attention. Three respondents acknowledged their own lack of attention to the curriculum change process, fearing that it might be their own fault that they didn’t have the basic information on the process although they try to stay abreast of the college news through e-mail. While not casting blame, the belief exists that faculty and staff should be informed even if they are not able to attend meetings. A few faculty members who are primarily research-based and a few staff members did not think they needed information on the process. However, staff members recognized the systemic nature of the work and were waiting for decisions in order to do their own planning. One basic scientist deliberately stayed away from the process:

“My whole goal… was to make sure that I wasn’t an active participant. My goal was to avoid getting sucked into another series of ongoing meetings with things that eat up time. I can just let other people do it.”

Curricular Elements. The majority of respondents did not have enough information about the five curricular elements that the Curriculum Review Committee had established as guiding principles. They recognized that it was difficult to gauge when they had enough knowledge about innovative practices that had not been fully developed. Others expressed personal concerns in not being able to teach or assess competencies.

“I don’t think we have spent enough time yet in really moving to a competency-based curriculum. There is a lot of work to be done. I think they’re going to need concrete illustrations of how the competencies will apply to what they’re doing. Pharmacology has a nice example of this.”

“I don’t know all the details of what competencies you want, but I’m in full support of them. I don’t understand how to teach toward competencies. I don’t know how to assess competencies, but I think it’s the right way to go.”

“I am aware of the national core competencies, but I don’t know how they will be integrated into the curriculum.”

However, some respondents expressed knowledge of the curricular elements. Several of the curriculum elements come directly from previous innovations and interests of individual faculty members. One respondent gave the interview team direction in terms of finding articles on curriculum change by other medical schools.

“Two of my issues—block exams and length of year—have been incorporated into the guiding principles. Everyone can incorporate some of these [elements], which I already do in the courses I direct. I do many things for the second year students that ‘they’ have no idea I do.”

“The Dean circulates Academic Medicine, and I pull out articles that I feel are germane. I have interests such as grading, lecture time, the value of lecture.”

Several respondents from the pharmacology and the neuromuscular medicine department already teach and assess from a competency approach.

“Understanding competency-based education is different from getting into the classroom. I have integrated several competencies: cost containment, professionalism, medical knowledge, and patient care. I should be more didactic about the competencies with the students. We also use several of the other elements.”

In order to move past awareness and informational concerns, one respondent advised that the college leadership for curriculum revision should remember new or returning faculty and staff who may be out of the loop.

“I came back after the process had already begun, and so I walked into the middle of it. I don’t know if there is a website or some resource where I could go to get the history, why we are doing the revision, who is involved, and the goals and objectives of the project. I would like to have information in some format—monthly newsletter with an update or website. I hate to take up someone’s time to catch me up.”

Personal Concerns (Stage 2)

Personal concerns are an important hurdle to overcome by college leadership and change agents and specific strategies and tactics are often less apparent than for other stages. The interviews confirmed the reason for high concerns regarding the personal impact of curriculum innovation. These concerns lacked focus because of the lack of knowledge and understanding for a large group of respondents.

Impact: Don’t Know. Given the lack of information reported by a majority of interviewees, it is not surprising that some faculty members were unable to predict how the curriculum revision process might affect them.

“I don’t know how it will affect me. I don’t know how to teach toward competencies, so I don’t know how that’s going to affect the way I teach.”

“I don’t know yet because I don’t have any certain information yet in regard to what changes might be recommended to the Dean.”

“I don’t have a clue. Obviously I always hope that it’s going to be for the better.”

Impact: Minimal. Staff members generally felt that the curriculum revision process would have minimal personal impact on them, while the majority of faculty members articulated a range of personal concerns about the process. Among interviewees who felt that curriculum revision would have minimal effect on them personally, the most common reasons were that potential changes did not apply to them or that they were already implementing elements of the proposed curriculum.

“I don’t see myself seeing any fundamental change, because I’m already on the same page.”

“We’re already looking at our information from an outcomes perspective and from a competency perspective from matriculation through residency.”

Impact: Strong. The remaining respondents shared a mixture of strong personal and general concerns related to the proposed curricular elements and their specific, defined effects. Two major areas of concern centered on reform efforts to integrate the national core competencies and to hold students accountable for course learning outcomes.

“The integration of the national core competencies, I think, is going to be real tough. . . . I think the two toughies are . . . the integration of the core competencies and the instruction based on learning outcomes.”

“I am fearful of the university interpreting the competencies just from their vantage point and not from the clinical standpoint.”

Although approximately one-third of respondents understood that one of the curricular elements was intended to make students more responsible for their own learning, faculty member views on the curricular elements of student choice and student accountability for learning varied widely. Comments in this area reflected the range of faculty experience with lecture alternatives, as well as their opinions about the ability of students to choose learning experiences and to be accountable for their own learning.

“I’m all in favor of alternative ways to learn. . . . I can’t write a prescription for the whole class that’s going to work equally well for all [students]. And they’ve got to be adults in the matter, to find what works for them.”

“I am not an advocate of adult learning theory. I feel these students do not have the skill set to decide they can learn better on their own and decide not to attend class.”

“We’ve essentially eliminated the lectures. There are people that don’t even come to lectures and do quite well.”

“I think it is important to have options open to the students to organize time and use it most effectively and efficiently. I think we have to accommodate different learning styles.”

Both clinical and basic science faculty noted resistance to change and faculty feelings of territorialism as potential areas of difficulty in revising the curriculum. Respondents cited both a general resistance to change and faculty members’ concerns about adequate curricular time for their subject matter as obstacles to be overcome in achieving proposed curricular changes.

“I think culturally you still have a lot of people on this campus who are in the mindset of that 50-minute block of time being how students get the curriculum.”

“It’s all about ‘this is the way I’ve always done it and this is my time and I’m not giving it up’ and we have a lot of work to do there.”

“I think the big challenge would be . . . that some of us would have to give up asking our pet [test] questions that reflect what we know and try to develop teaching and learning questions that reflect what students need to know.”

Interviewees identified a need for faculty development targeted to assist faculty in applying the planned curricular elements to their actual teaching situations. Activities that model the desired teaching methods and provide opportunities for faculty to develop teaching skills and evaluation methods that have immediate application were most requested.

“I need someone to . . . give me an exact example. I want someone to send me to a resource or show me how I can go from start to finish and fit into that competency picture. I also don’t know how to assess competence. And I would like specific examples as opposed to general concepts . . . . I would not want to have to attend weeks upon weeks of lectures to learn that; I’d want to keep it to a minimum.”

Another recurring theme was a concern with personal time, both as a limited commodity and as a necessary ingredient for successful curriculum change. Both clinicians and basic scientists expressed concerns about multiple demands placed upon faculty by the proposed curricular changes. One basic scientist summarized it this way:

“When you start talking about small groups, you start talking about clinical relevance, you’re talking about a lot more preparation and more faculty members. You need enough faculty members to sit in small groups and have a decent ratio to facilitate attentive students. [Clinical faculty] face similar challenges in terms of having more intimate relationships with students.”

One fourth of respondents expressed concerns about time, ranging from whether curriculum changes could be accomplished in the time allotted to how time would be allocated among courses and whether expectations of faculty were reasonable and achievable. Faculty also pointed out that different faculty subgroups – clinicians, basic scientists, full-time, part-time and volunteer faculty – face various challenges in undertaking curriculum revision.

“I feel the issue that has not been addressed is: How much time is allotted to topic areas? This is driving everything else and needs to be addressed.”

“It is always hard to get clinicians to change how they approach education. It is a long arduous task to revise lectures, based on the new WebCT™ paradigm. It is going to take a long time to get these fine-tuned.”

“To expect [volunteer faculty] to spend that amount of time away from practice is unrealistic.”

“The university needs to understand that with faculty who are trying to maintain clinical practices, there is only so much that we can do, and it doesn’t mean that we can or should be ignored in the process in making fundamental changes.”

“It will be easy for the university to push training by the clinicians out of the 2nd year into the 3rd year and not give us the resources to bring it to fruition. Yet there won’t be enough time in the curriculum to teach these students what they need to know—more educational requirements, less time.”

Management (Stage 3)

Interviewers asked each person to think of the management implications of changing from current practice to incorporation of five new curriculum principles. Interviewees were very forthcoming in discussions about management issues, and analysis revealed a set of concerns. These findings showed clear thematic issues of resources, faculty and student time, assessment and evaluation, and faculty development, as well as leadership and accountability.

Resources. One-third of all respondents, among both clinical and basic science faculty, were concerned about the financial needs of the college as related to supporting a new curriculum and delivery system, particularly what was defined as an unfunded mandate. They were concerned that the lack of a strong overall national economy would affect the college and its clinical offices directly. One respondent cited a need for grant writing support at the university level and a reliable business office. Another respondent identified the added costs for small group facilitators when moving away from lecture teaching as the new curriculum recommends. One respondent saw a different side of the issue when a perception of limited resources becomes a belief that undermines change, even when not based on accurate information.

Personnel needs were the second and a closely-related resource concern. Basic science instructors asked for technical staff to execute the new curriculum scheduling software and to support faculty who use the WebCT™ course management system. Since WebCT™ is a tool for accomplishing several of the design elements, the faculty want someone to support them, not just train faculty members to do the work, believing that organizing the course website and uploading documents is not a productive use of faculty time. One respondent suggested that faculty should deal with content, sequencing and instruction, not the mini-details of technology use in curriculum delivery.

The Curriculum Office is an important operational office with responsibility for schedules, contracts and student assessment. Their operations received both kudos and caveats that related to resources.

“The curriculum office is basically overwhelmed. We haven’t replaced people who left. It seems that they are having a hard time keeping up with things the way we do it now, much less making a huge transition. They need more personnel and better software.”

“It all comes down to not only money, but somebody who’s competent to run the new technology.”

Faculty and Student Time. Basic science faculty members were intensely concerned about time, both for faculty and students, as a management element. Respondents noted several key concerns: curriculum change and assignments have been incremental; there is no systematic structure for setting faculty load; and faculty time is often allocated to several degree programs. System course managers are particularly confused by the load obligations. In addition to these larger time issues, one respondent explained that instructors are simply trying to meet daily demands.

One of the first and most visible steps in the curriculum revision process was to shorten the academic year. Because of management constraints, the new calendar was posted in advance of the development of new curricular options including electives and remediation. Although mentioned in the management section of the interview, some responses reflect informational and personal concerns as well.

“The schedule change is about all that people know about the process. The pedagogy, competencies, [learning] outcomes – they don’t know about that.”

“Will faculty involved in remediation or electives need to cut back on their research/scholarship or service to the university/profession?”

“Will the competency approach and the new calendar bring out space issues?”

“If we reduce classroom time, everybody needs to hold the line. In the past, there have been issues of extra classes, review sessions, and such that became a ghost curriculum. There is also competition for time between disciplines.”

Respondents pointed out that the shorter academic year meets the perceived student demand for dual degree options. Faculty respondents were concerned that the shorter academic year would negatively impact students, but also acknowledged that students will have new responsibilities to come to class prepared.

“The student time would be my primary concern because I don’t know how to estimate well. We can’t have unrealistic expectations in the first two years. The rationale to determine content makes sense; however, it must be manageable for the students.”

“If you are doing a case, students will need to read the material before entering class and come prepared.”

“When the student is responsible for the learning outcomes, the information is there even if there is an instructor illness or emergency or snow day. It has given them better options for the use of their time.”

“I get concerned about teaching the appropriate information at the appropriate time. We have to teach for their stage of education.”

Assessment and Evaluation. Competency-based education calls for new approaches to student assessment and program evaluation. Concerns arose when the Curriculum Review Committee recommended having block exams, and faculty struggled with the impact on students. Some basic science and clinical professors noted the first step in changing learner assessment is based on a continuum of competency levels from medical school through residency. There were again concerns about resources.

“Do we have the resources to increase the amount of curriculum that’s available on the Internet, handle all of our remediation, change the schedule for the summer, and change the tests and measures that we have?”

In order to manage the process, respondents made several suggestions related to management of the assessment and evaluation process.

“We need to get documentation of grades, both preclinical and clinical, in a timely fashion for the Dean’s letter to be completed.”

“The college needs a new computer software system that also reports curricular units to accrediting bodies.”

“Improved evaluation and more timely feedback can lead to evidence-based education.”

Faculty Development. The challenge of curriculum change was seen as an opportunity for systemic faculty/staff development. One respondent explained that adopting the new perspective of core competencies requires that all course managers ‘see the whole picture.’ Faculty respondents also requested more specific training in exam development and test item construction. Both basic science and clinical professors acknowledged the problem of ‘refuseniks’ and recommended giving support to those who are really interested in making curricular change. In addition to training workshops, one respondent recommended that faculty move beyond the traditional department meetings in order to both learn and develop the competency curriculum.

“It would be nice to get the first year course directors together periodically and talk about things.”

“We need cross department meetings of all 1st year teachers and all 2nd year course managers.”

External clinical lecturers present a challenge for faculty development that is geared toward the implementation of competency-based curriculum.

“House people are making a list of what students should know, but lecturers are coming in and sometimes their lectures match and sometimes they don’t. At the same time you are implementing WebCT™, you’ve got instructors coming in from the outside that don’t know the system.”

Leadership and Accountability. The interview process focused on an understanding of the curriculum revision process and the proposed curricular elements. The question of management brought to light concerns about leadership. Individuals complained that they received mixed messages from the leadership and that there was poor coordination of the process. Respondents recommended that the leadership should recruit, support, and capture people interest in the curriculum revision process.

Respondents reflected on past problems with the lack of authority by the college curriculum committee because it does not function as an oversight committee. They recommended a new unit to manage the seamless integration of all five curricular elements, managing both the policies and the logistics. The person in charge of this unit would have leadership and management of the overall look of the curriculum and the delivery as well. However, there were differences in identifying the criteria for this unit leader.

“The person needs to know where everything is in the curriculum and how it builds to the competencies – all in one place. This person needs to have credibility with the people in the trenches trying to implement this curriculum.”

“I see a new curriculum office…headed up by a PhD or some doctorate level person. Somebody clinical could come who doesn’t want to practice any more but may want to get into education. Or maybe it could be a basic scientist who could organize lots of stuff in the curriculum. It can’t be someone who is too theoretical.”

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The SoC questionnaire and the personal interviews were a two-pronged approach to formative evaluation. The questionnaire showed a profile very similar to the typical non-user; therefore, our institutional profile gave us an appropriate baseline for future evaluation. The interviews cast the spotlight on themes that more fully explain the SoC Questionnaire data. The analysis is also significant in helping the leadership determine who is ready for change in a mature institution. From a concerns approach, curriculum leadership must first design strategies to address lower-level concerns such as informational and personal concerns, in order to allow faculty and staff to focus on higher-level concerns of management, consequence, and collaboration.

Interview findings of awareness and information needs were highly consistent with the findings from the SoC profile, which told us that almost all of the responding faculty had an awareness of the reform effort, but few felt that they actually knew what was going on with the curriculum reform. The faculty and staff continue to ask why we are changing if our graduates have done well. There has been no apparent conceptual bridge formulated connecting new professional roles in the national medical system to competency-based medial education. Therefore, the leadership needs to stress the driving forces for curriculum change and establish urgency for the process. The larger picture of competency-based education, including the set of curriculum design elements, was lost when the first visible sign of change was the shorter school calendar without concurrent offerings of summer electives, research opportunities, and remediation. Even those on the Curriculum Review Committee did not recognize the five curriculum design elements as a road map that was generated from hours of discussion in meetings. It is clear that there was no trickle-down effect. Information about both process and decisions needs to be shared in multiple formats and venues and repeated throughout the multi-year process.

The SoC questionnaire showed intense personal concerns. Our analysis of interviews showed a dominant theme of “us versus them”. While this mentality may seem unavoidable because of distinct points of view, everyone should be focused on the successful medical student and resident. So, we ask, how do we break down barriers between groups that fluctuate by role — between clinical and basic science faculty, between curriculum committee members and other faculty/staff, between administration and faculty, between faculty and medical education specialists? We have changed the COM Faculty Assembly to an evening time slot to encourage participation by clinical faculty. Each clinical department has worked with the MS2 System Course Manager to analyze the course disease index using the criteria of commonality and criticality. The first year Biochemistry course was redesigned to use team-based learning and case-based curriculum with clinical faculty contributing cases and test items.

During the interviews we learned that faculty were unsure how the curriculum design elements would impact them personally, in part because at that time the design elements had not resulted in specific curriculum changes. People who had changed their course to focus on student learning outcomes seemed to think that they were already finished with curriculum change, although their instruction and course assessments may not have changed to learner-centered approaches. A deeper analysis of the interview data indicates faculty insecurity about being successful given the high level of student choice recommended by the curriculum design elements. Faculty members will have less control over the student learning experiences, but expect that the faculty will still be held accountable for student failure. They appear to have little faith that students will actually be held accountable for their own failures. The interviewees gave very specific ideas for needed faculty/staff development related to the curriculum design elements, moving beyond workshops toward demonstration and mentoring. Personal concerns were frequently intertwined and expressed in terms of institutional culture as well as faculty prerogatives. When interviews were analyzed as a whole rather than by individual question, it became clear that initial policy making was critical to the process. The work of curriculum revision requires extension beyond the major committee to a variety of working committees that brings larger numbers of faculty and staff into the process.

The results of the SoC showed a higher concern for personal issues than for management issues; however, the interviewees spent far more time discussing institutional and curriculum management concerns than truly personal concerns. This may be a result of the way that the SoC items are written, a function of the sample, or a function of the faculty member unwillingness to talk about themselves versus their desire to discuss institutional problems that may have been on their minds for some time. Collaboration, as shown by the SoC Questionnaire, was not a strong concern at this stage of the process.

Respondents viewed both additional faculty and support staff as necessary resources to successfully carry out the planned curriculum changes; they also believed that high quality technical support services would be essential in implementing new technologies and sustaining them once adopted. The respondents were clear that the need for resources, both financial and otherwise (personnel, leadership), requires setting priorities at both university and college levels. Resistance to curriculum change often comes from a lack of confidence in the institution being able to meet these resource demands. People recognize that time is also a critical resource that must be managed effectively. Current and future demands on faculty load have not been factored into the plan for curriculum redesign. Demonstration of competency requires extensive and expensive learner assessment and holistic program evaluation, which creates stress within the curriculum system and requires new technology for reporting and feedback. Under the theme of management, the issue of curriculum change has also challenged the current curriculum governance structure. With current changes in institution and college administration, the curriculum process and governance has become even more critical.

Our institution is not alone in struggling with curriculum reform. Other researchers have studied the process of curriculum change. Bernier and coworkers5 describe experiences of two medical schools over a period of three to four years. Each school changed from a traditional, lecture-based, decentralized, department-based curriculum to a centrally governed, integrated, student-centered curriculum evoking greater collegial relationships among students, faculty and administration. Three lessons were cited as being key to the success of curricular change. First, a broad commitment to change was led by each dean and central administration and reinforced by national education policy and philosophy. Second, widespread inclusion of faculty and students in the process enhanced the willingness of the faculty to cede authority to a new curriculum committee before the design of the curriculum was complete. In addition, the establishment of a centralized governance system early in the process resulted in a strong, empowered curriculum committee with implementation support from the Office of Medical Education.

Our analysis was confirmed when we attended the 2005 annual conference of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM). Dane and Kreuger16 reported on the curricular change process. Peter Dane (OU/COM) described the tripartite leadership that comes from the Dean, a centralized curriculum authority, and a team of champions who work beyond the basics. He stressed the need for clarity of purpose, describing the philosophy and rationale for their movement toward a new curriculum that was distributed widely in the form of a white paper. He reminded curriculum change agents to honor the present and the past while nurturing seasoned educators. He advised special care of students during the transition year. Paul Kreuger (UMDNJ/SOM) identified four keys to curricular change success that relate well to the stages of concern: a clear mission, strong leadership, adequate resources, faculty and faculty development.

Although ours is a single site, formative evaluation study, many medical educators may see similarities to their own experiences with curriculum revision. Furthermore, the concerns approach and the SoC instrument as well as the findings offer practical information to leaders whose institutions and academic programs are soon to begin curricular change. From our study and the efforts of others, we have learned the importance of setting up a curriculum revision process based on both individual and institutional concerns that have potential for influencing the development and implementation of a new curriculum. The process needs to be systematic with timelines and responsibilities. Everyone needs to be kept informed of the process and the outcomes of deliberations with information coming in multiple formats including a website, hallway bulletin boards, and written materials, as well as key descriptive and research articles. Care should be taken to release information in a logical fashion so that faculty and staff not directly involved in the development stages can understand the reasons for current plans and have an opportunity to respond if they are unhappy with plans at any given stage. Additional resources will be needed to be successful, including: qualified assistance with effective use of WebCT™, grant-writing support, faculty coaching, and implementation of effective evaluation approaches. Understanding the stages of concern can result in more targeted strategies, more relevant workshops, and directed planning to implement the new curriculum plan thereby creating successful, institutionalized change.

REFERENCES

- Hall, G.E., and Hord, S.M. Implementing change: Patterns, principles, and potholes. Boston. Allyn and Bacon. 2001.

- Hall, G.E., and Loucks, S.F. Teacher concerns as a basis for facilitating staff development. Teachers College Record. 1978; 80(l): 36-53.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation. A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979.

- Lewis, D., and Watson, J.E. Nursing faculty concerns regarding the adoption of computer technology. Computers in Nursing. 1997; 15(2):71-6.

- Gwele, N.S. Concerns of nurse educators regarding the implementation of a major curriculum reform. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996; 24:607-14.

- Arwer, J.M., Harris, K., and Dusold, J.M. Application of the concerns-based adoption model to the installation of telemedicine in a rural Missouri nursing home. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2004; 20:42-9.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979, p. 23.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979, p.24,26.

- Eisner E. The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and enhancement of educational practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall. 1998, p. 110.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979, p. 78.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979, p.39-40.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979, p. 72.

- Hall, G.E., George, A.A., and Rutherford, W.L. Measuring stages of concern about the innovation: A manual for use of the SoC questionnaire. University of Texas at Austin, 1979. p. 73.

- Bernier, G.M., Adler, A., Kanter, S., and Meyer, W.J. On changing curricula: Lessons learned at two dissimilar medical schools. Academic Medicine. 2000; 75:595-601.

- Dane, P. and Kreuger, P. Leading Curriculum Change: Looking Forward, Looking Back. A presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Bethesda MD, June 2005.