ABSTRACT

Technology is increasingly used in medical education. This study describes student and faculty attitudes toward and use of tablet PCs, electronic textbooks, and video podcasts in a technology-enhanced integrated curriculum.

A survey concerning the use of technology was collected at the end of each semester for the graduating class of 2010. Faculty completed a technology survey at the middle and end of the second year. Analyses consisted of descriptive statistics and proportional analyses were used to determine significant differences.

Most students took lecture notes directly on the table PC with less than 3% using paper and pencil. The use of specialized note taking software dropped over time from 73% to 51%, while the use of Microsoft Word increased from 5% to 16%. Students that wrote notes directly on the tablet PC remained relatively constant, while those that typed increased from 38% to 60%. Podcasting of lectures was popular, but lecture attendance dropped over time. While student preference for electronic textbooks increased over time, most students would buy print or a combination of print and electronic textbooks. Most faculty reported that having computers in learning activities enhanced the learning process and indicated that the electronic textbooks were easy to integrate into their learning activities.

Students and faculty were generally satisfied with the technologies and the student use of the technologies changed over time. If technology can enhance the learning environment, then we should embrace it because our students have.

INTRODUCTION

Students come to medical school with increasing knowledge about technology. Most current medical students are part of what has been called the Net Generation, a cohort of young people born between 1982 and 1991 that have grown up with information and communication technology.1 This cohort tends to use a computer daily, regularly goes online, and is active in online social networking websites. They also tend to be highly connected to their peer group, especially through the use of mobile phones, Internet chat rooms, instant messaging, blogs, and wikis.1

Since current medical students tend to be more technologically savvy than their predecessors, they may learn in fundamentally different ways from previous generations. Oblinger and Oblinger2 suggested that the Net Generation is more comfortable with multimedia environments, prefers to actively engage in tasks rather then merely reading about them, are avid users of technology, and expect immediate responses. They are achievement-oriented and prefer a clear learning outcome to a task. They expect technology to be a part of their educational environment and expect their instructors to have the ability to utilize technology to enhance their learning.2

There has been considerable research on web-based or Internet-based learning in the health professions with recent reviews finding well over 200 published articles on the topic.3,4 Although research comparing the effectiveness of Internet-based learning compared with non-Internet instructional methods has found varied results, a recent meta-analysis concluded that Internet-based instruction yields similar levels of learning as that of more traditional instructional methods.4,5 Continued research on the impact of technology on learning is clearly important. However, the focus of this paper is on how students view and use technology in their learning.

A recent literature review of information and communication technologies in higher education suggested that technology fosters information presentation, provides for efficient assessment, can foster collaborative learning and that computer simulation can be helpful especially for novices.6 Other studies have focused on student opinions. Several of these studies have reported that medical and nursing students are highly satisfied with podcasting (i.e., a digital recoding of the lecture that can be played back on a computer or portable player) of lectures7,8 and actually prefer reviewing recorded lectures after the lecture rather than listening live to a simulcast lecture on a computer.7 Billings-Gagliardi and Mazor9 explored whether lecture attendance would change as a result of students having access to lecture materials electronically. They reported that access to electronic course material did not impact lecture attendance. Another study investigated the use of electronic books and tablet personal computers (PC) for content distribution and note taking in a dermatology course. Although students thought the electronic books were an effective way to distribute course material and for studying, they preferred to take notes on paper.10

The University of Kansas School of Medicine recently developed an integrated, technology-enhanced medical curriculum to begin to address the learning needs of the Net Generation. The curriculum is organized into system-based modules, rather than the traditional discipline-based courses, with lectures in the morning and interactive small groups, problem-based learning (PBL) groups and laboratories in the afternoon. The centerpiece of this new curriculum is the student requirement for a tablet PC upon matriculation. The lecture halls are equipped with both wired and wireless Internet access. The tablet PC includes a standard hard disk image, with Microsoft OneNote11 and Agilix GoBinder12 note taking software that allows students to type on the keyboard or write directly on the screen using a stylus and electronic ink. The note taking software also allows students to organize their own files and to search for any term that was typed, written or stored on the computer. This process lets students actively organize the material to enhance their studying and learning styles. All lectures are saved in a video digital format that allows students to review the lecture on a PC or a portable player. All course content (e.g., objectives, slides, formative quizzes, grades, etc.) is provided in electronic form and can be accessed directly from a shared network drive or through the Angel learning management system13 either on or off campus.

For online text and reference material, the library licensed the web-based AccessMedicine14 suite for the entire medical center. The School of Medicine purchased additional electronic textbooks from Elsevier and from Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins as a 2-year pilot project for the medical students. These additional electronic textbooks were installed on each tablet PC hard drive and are accessed through the VitalSource reader.15 Histopathology labs were conducted using the Aperio microscope-simulator system16 that allows students to move around a scanned microscope image, zoom in and out, annotate, and save images, in order to create their own histopathology atlas. A computerized testing center was built to allow students to take exams electronically and provide immediate feedback concerning their exam performance. Finally, an enterprise-level dedicated electronic survey development system from Vovici17 was purchased for curriculum and program evaluation.

The purpose of this project was to identify how students use the technologies in medical school, understand their attitudes towards the technologies, and to track changes in attitudes and usage of the technologies. Another purpose was to evaluate the attitudes of faculty toward the technologies and their opinion of the impact the technologies have on the learning activities in which they participated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The graduating class of 2010 and the faculty that instructed them were asked to participate in the curriculum evaluation project. There were a total of 181 students in the class, which was comprised of 53% males and 93% Caucasians. The average age was 25.92 years (SD = 4.40 years), with 66% being born between 1982 and 1991 and 82% born between 1980 and 1991. A total of 146 faculty participated in the instruction of the class of 2010 (e.g., lecturers, PBL facilitators, small group and laboratory leaders, etc.) and were asked to take part in this project.

Procedures

An online survey asking students about their use and attitudes toward their tablet PCs, electronic textbooks, lecture podcasts and other technologies was collected at the end of each semester for the first two years of medical school, yielding 4 data collection points (i.e., Fall 2006, Spring 2007, Fall 2007, and Spring 2008). Faculty completed the online survey at the end of the Fall 2007 and Spring 2008 semesters. Participation was voluntary for all surveys and all responses were completely anonymous. This project was reviewed and approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Surveys

The student survey was developed by a committee of medical educators, faculty and technology experts as part of a larger technology survey used to evaluate student opinions and use of the technology within the curriculum. Questions focused on ease of use, frequency of use, and how selected software and/or devices were used in the curriculum. Some questions were also concerned with preferences for electronic versus non-electronic methods, usefulness of the technologies, or how the technology impacted their behavior. The faculty survey was developed by the same committee and focused on faculty observations and opinions of the impact of students having computers in their lectures and small groups, and having access to podcasts of their lectures. In addition, the faculty survey asked about their preferences for electronic versus traditional methods for teaching purposes. All questions utilized either a 4- or 5-point Likert response scale. Since the items varied in response format and the survey is anonymous, it is difficult to get an adequate reliability estimate for the survey. As such, there is no reliability information available for the surveys.

Analyses

Preliminary analyses included independent t-tests and chi-square analyses to check the representativeness of those students that responded to the surveys to those that did not respond. Additional analyses which consisted of descriptive statistics and proportional analyses were used to determine any significant differences. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 15.018 and Microsoft Excel 2003.19

RESULTS

The response rates for the four data collection periods were 34% for Fall 2006, 43% for Spring 2007, 37% for Fall 2007, and 32% for Spring 2008. Preliminary analyses conducted separately for each data collection period comparing students that responded to the survey with those that did not, failed to demonstrate any significant differences between the groups in terms of ethnic make-up, performance as measured by semester grade point average and average age (all ps greater than 0.05). One gender difference was noted for the Spring 2008 semester with significantly more females responding then males. Assuming that the above characteristics are related to attitudes toward technology, the mostly non-significant findings suggest that the results for those that responded to the survey may generalize to the entire class. The response rate for the faculty survey was 52% for Fall 2007 and 39% for Spring 2008.

Note Taking

Students: Students were asked to indicate their primary note taking preference. The options included; paper-&-pencil, GoBinder/OneNote, Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, Other. Across all semesters, the majority of respondents (51% or more) took notes on the tablet PC using specialized note taking software while less then 3% indicated using paper and pencil to take notes. The use of note taking software dropped significantly over time from a high of 73% in Fall 2006 to a low of 51% in Fall 2007 (z = 2.51, p = .01) and 53% in Spring 2008 (z = 2.23, p =.03), while the use of Microsoft Word significantly increased from about 5% in Fall 2006 and Spring 2007 to 16% in Fall 2007 (z = 2.78, p = .005) and 15% in Spring 2008 (z = 2.45, p = .01). The use of PowerPoint as a note taking tool varied between 20% and 30% across the semesters.

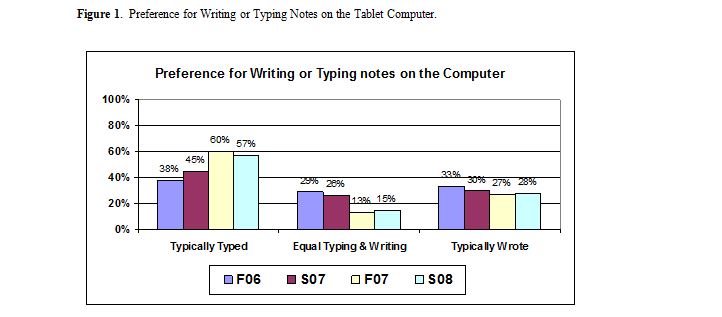

Students were asked to indicate their preference for writing on the tablet PC or typing on the tablet PC for lecture note taking with the following options; almost always typed, mostly typed with some writing, about equal typing & writing, mostly wrote with some typing, almost always wrote. Results for Fall 2006 indicated that 33% typically wrote on the computer using the stylus, 29% did about an equal amount of typing and writing on the tablet, and another 38% typically typed their notes. As shown in figure 1, as the class moved to the second year, (i.e., Fall 2007 semester) those that typically wrote on the computer remained about the same at around 30%; however, those that typed significantly increased from 38% (Fall 2006) to 60% (Fall 2007; z = 2.38, p = .02) and 57% (Spring 2008; z =2.06, p = .04).

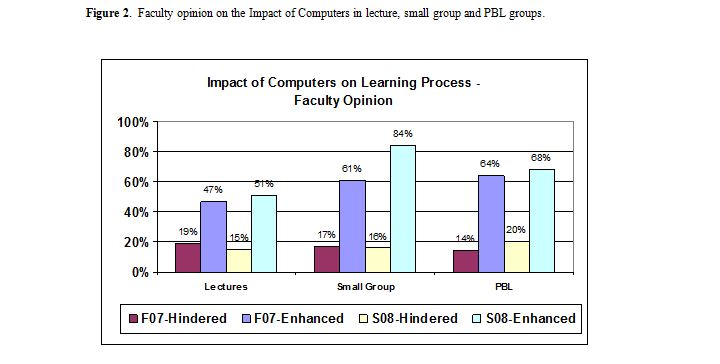

Faculty: Faculty were asked what impact the presence of tablet PCs in lectures, small groups and PBL groups had on the learning process with the following options: severely hindered, slightly hindered, no difference, slightly enhanced, significantly enhanced. About half (47% for Fall 2007 & 51% for Spring 2008) of the respondents indicated that having computers in their lectures slightly or significantly enhanced the learning process, while 19% during the Fall semester and 15% for the Spring thought it slightly or severely hindered it. For small group activities, 61% of the Fall respondents and 84% of the Spring faculty polled reported that having computers enhanced the learning process, while 17% or less thought computers hindered the learning process. Finally for PBL groups, about two-thirds of the respondents across both semesters noted that having computers in PBL enhanced the learning process, while 20% or less thought computers hindered the learning process in PBL groups for both semesters. No statistically significant differences between the two semesters were noted for the faculty ratings. Figure 2 presents these faculty data.

Podcasting Lectures

Students: Students were asked how often they used video podcasts on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to daily. Video lecture podcasts were popular with at least 58% of respondents indicating that they reviewed podcasts at least weekly across each semester. Only 5% or fewer indicated never reviewing a podcast. Students were also pleased with the video podcasts as evidenced by 87% or more of the respondents reporting being satisfied or very satisfied with podcasts regardless of the semester in which they completed the survey.

or more of the respondents reporting being satisfied or very satisfied with podcasts regardless of the semester in which they completed the survey.

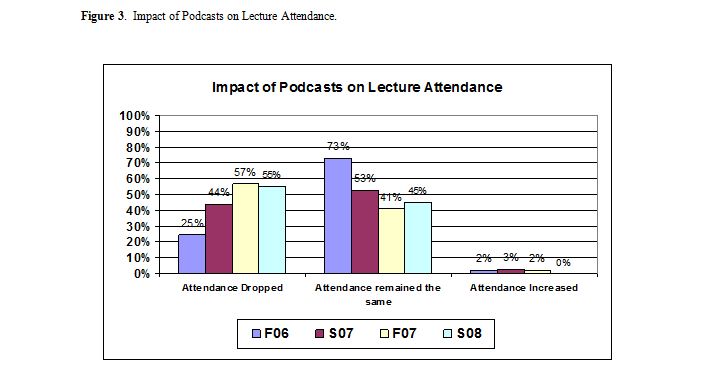

Students were asked how podcasting impacted their lecture attendance on a 5-point Likert scale which was combined into three groups (i.e., dropped, remained the same, and increased) for analysis and are summarized in figure 3. Reported lecture attendance significantly dropped as students moved through their first year and into the second year of medical school. In Fall 2006, 25% indicted that their lecture attendance dropped as a result of reviewing podcasts and in Spring 2007, 44% noted a drop in lecture attendance and by Spring 2008, 55% reported that their lecture attendance had decreased (25% less than 44%, 57%, & 55%; all ps less than.05).

Faculty: Faculty were asked their level of agreement with the statement “Podcasting of lectures was valuable for students” on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Across both semesters, 62% of the faculty polled agreed or strongly agreed that lecture podcasts were valuable for the students, while 6% disagreed or strongly disagreed. Thirty-three percent were neutral about the value of podcasting lectures.

Electronic Textbooks

Students: Students were asked about their level of agreement with the statement “AccessMedicine was easy to use” and “VitalSource etextbooks were easy to use” on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The majority of respondents (63% to over 90%) across the semesters agreed or strongly agreed that the web-based AccessMedicine electronic resources and VitalSource electronic textbooks were easy to use. In addition, ease of use increased as students used them overtime. Although the ease of use of the VitalSource textbooks increased over time, the percentage of respondents that reported using VitalSource textbooks at least weekly remained relatively constant over time at about 32% with a slight increase in Spring 2008 to 42%. Similarly, the percentage of student respondents that reported using AccessMedicine resources at least weekly remained relatively constant at about 32% over time with a drop in use during Spring 2008 to 15%. Students preferred the VitalSource method of access to electronic textbooks over the web-based access of AccessMedicine (61% greater than 39%, p less than .001). Significantly more respondents used AccessMedicine for quick reference as compared with the VitalSource electronic textbooks (67% greater than 53%, p = .006), while significantly more students used the VitalSource electronic textbooks for in-depth reading and studying (38% greater than 24%, p =.006). Finally, about 70% of respondents, regardless of semester, indicated that the ability to search electronic textbooks contributed to their use.

Students were asked if they bought or printed any electronic textbooks that were provided. Across all four semesters, 60% or more of the respondents indicted that they had not printed any textbooks. As concerns purchasing textbooks, only about 20% of respondents reported not buying printed versions of the provided electronic textbooks. The specific electronic textbooks purchased changed as students moved through the curriculum from pathology and anatomy books in the first year to embryology books in the second. Several students noted checking books out from the library or borrowing from upperclassmen rather then purchasing them. Reasons for not using electronic textbooks included technical problems that dropped from a high of 27% to under 14% by the second year, a preference for printed textbooks that varied from 25% to 43%, eye strain from reading too much on the computer, and needing a break from the computer, since it was used for everything in the curriculum.

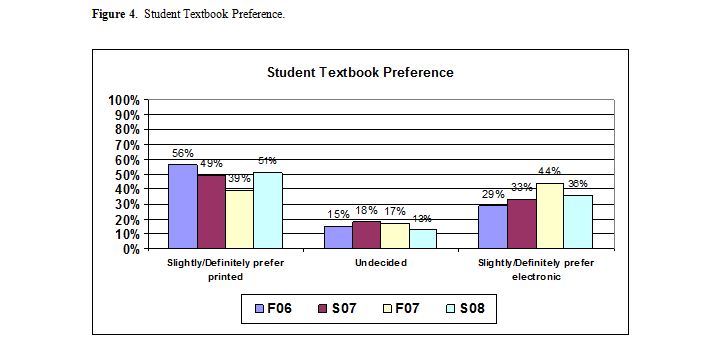

Students were asked whether they preferred electronic over printed books, were undecided, or preferred printed over electronic books. Student preference for printed or electronic textbooks is presented in figure 4. Although their preference for printed textbooks dropped during the first three semesters 56% to 39%, the decrease was not significant (z =1.87, p =.06), and their preference for printed texts increased to 51% during the last semester. Similarly, student preference for electronic textbooks increased during the first three semesters 29% to 44%, but the increase was not significant (z =1.72, p =.09) and their preference for electronic texts decreased to 36% during the last semester. Students were also asked if they had to buy textbooks today, would they purchase printed or electronic. During their first year of medical school, 40% to 47% of respondents would probably or definitely buy printed textbooks and during their second year 41% to 44% would still purchase printed textbooks. Purchasing electronic textbooks averaged about 15% across all semesters and approximately 40% of respondents across all semesters would purchase a combination of printed and electronic textbooks.

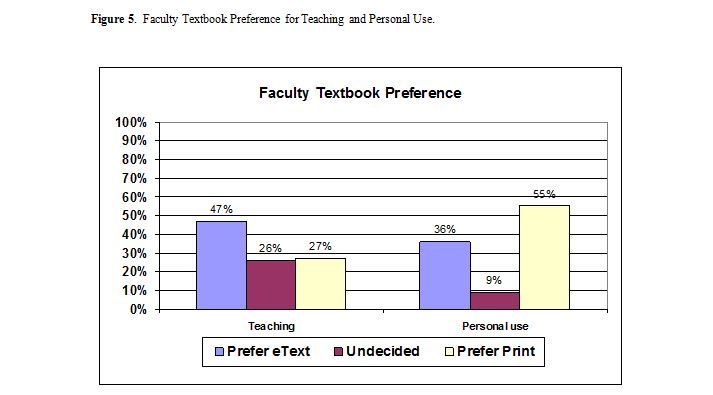

Faculty: Faculty were asked their level of agreement with the statement “Electronic textbooks were valuable for students” on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The majority of respondents (59% for Fall 2007 & 57% for Spring 2008) agreed or strongly agreed that electronic textbooks were valuable for students with 12% or less disagreeing. A majority of faculty respondents (65%) across both semesters indicated that electronic textbooks were easy to integrate into their learning activities, while 18% disagreed. Faculty were also asked their preference for printed or electronic texts for teaching and personal use. Figure 5 provides the results for these questions. For teaching purposes, significantly more respondents across both semesters preferred electronic texts (47%) to printed textbooks (27%, z = 3.07, p =.002). For personal use, significantly more respondents across both semesters preferred printed texts (55%) over electronic (36%; z = 2.68, p = .007).

DISCUSSION

Students readily accepted and used the technologies introduced by the curriculum, and their use of the technology tended to change as they became more experienced with it and with the increasing demands of medical school. Initially, the majority took notes on the computer using special note taking software, but over time many switched to taking lecture notes with Microsoft Word. Similarly, although most students took notes on the computer either writing, typing or in combination, over time, the majority of students typed their notes on the computer. These results conflict with those of Morton and colleagues10 who reported that medical students preferred to take notes on paper. The differences between the two studies may account for the discrepant results. In the Morton et al.10 study, students in one course volunteered to participate in a study that used computers and electronic textbooks. The authors stated that while many courses have web content, there was no centralized electronic course management system. Further, the electronic resources were introduced 1.5 years into the curriculum and only for one week. In our curriculum, all of the content for the first two years is digital. All students have the same tablet PC, and must access course content on-line. Notes must be taken in some sort of electronic format if students want to be able to search their notes and easily integrate them with other content. Therefore, our curriculum structure strongly encouraged electronic note taking.

Podcasting of lectures was popular among students with only 5% never reviewing a podcast. However, students also indicated that one impact of the podcasting of lectures was a drop in attendance. Attendance decreased as students moved through their first year and into their second year of medical school. We have asked students about their lecture attendance for years without podcasts and from these previous surveys about 80% of first year students indicated attending most lectures, while only 59% of second years noted attending most lectures. Extrapolating the impact of podcasting on lecture attendance from these numbers suggested that the biggest drop occurred in the Spring semester of the first year with about 27% attending fewer lectures as a result of podcasts and about 16% of second year students attending less lectures because of podcasting. A drop of 1 in 4 students for first-year and 1 in 6 for second year suggests a relatively large impact of podcasting on lecture attendance. These findings are in contrast to previous research that did not report a meaningful change in attendance as a result of students having access to electronic course material.9 Because our findings are self-report only, additional research with accurate lecture attendance tracking is needed to better determine the impact of podcasts on lecture attendance and more importantly, performance in medical school.

In general, electronic textbooks were easy to use with ease of use increasing over time. Although ease of use increased with repeated access, frequency of use remained relatively stable over the two years. Students preferred the VitalSource textbooks stored on their computers over the web-based AccessMedicine textbooks. Students used the textbooks in different ways. The VitalSource textbooks tended to be used for more in-depth reading and studying, while the AccessMedicine web-based texts were used more frequently for quick reference.

The majority of students did not print paper copies of any of their electronic textbooks, but many did purchase printed versions. Although student preference for printed or electronic textbooks tended to change over time, there were no meaningful differences noted across the two years. At the end of the second year of medical school, the majority of students would either buy paper or a combination of paper and electronic textbooks. Technical problems, eye strain and needing a break from the computer were some of the reasons cited by students regarding their lack of use of electronic textbooks. Other comments revealed that previous use and comfort with traditional paper and pencil textbooks for studying and learning also limited the use of electronic textbooks. For the current class cohort, electronic textbooks were a nice option to have, but may not have been their first choice for learning. As students enter medical school with more experience with digital information and more experience with electronic textbooks, and as the technology improves, student preference for and purchase of electronic textbooks may likely change. To this end, longitudinal research tracking the use of electronic textbooks along with the advances in the electronic textbook technology should be conducted.

Since students were taking notes during lecture, the attitude of faculty towards having computers in class was also evaluated. Less than 20% of faculty polled for both semesters indicated that having computers in the classroom hindered the learning process. In fact, the majority of faculty polled reported that having computers in small group and problem-based learning activities enhanced the learning process. In addition, the majority of faculty respondents noted that podcasting of lectures and electronic textbooks were valuable for the students. Most faculty respondents indicated that the electronic textbooks were easy to integrate into their learning activities. Finally, for teaching purposes more faculty preferred electronic textbooks over printed, but for personal use more faculty preferred printed over electronic textbooks.

Although the majority of the faculty that responded indicated that the technologies enhanced the learning process, the exact nature of the enhancement is unknown since the question was designed to elicit overall general opinions. Therefore, it is also unknown what the “hindrances” may be to the learning process. Some of the “hindrance” to the learning process may be that the faculty tends to be less technology savvy then the students and did not use computers in the classroom when they were students and as such they may be resistant or reluctant to change. Nevertheless, additional research with more specific questions and focus groups may allow for more detailed explanations of these results.

These results must be interpreted in light of the limitations of this study. The sample consisted of one class from a single medical school and the response rates, although representative for the class, were relatively small. Therefore, these results may not generalize to other classes or other schools with different student demographics. As students enter with more technology experience, their views and use of technology may well be different from this cohort. The small response rate also suggests that only relatively large differences would emerge as significant. In addition, it is possible that those that responded were more technology-savvy then those that did not and this may have introduced some bias into the results. Another limitation is that the questions were written to elicit general opinions, so clear explanations for some of the results were not possible.

One reason for using the technologies was to better meet the needs of our students; however, the United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1 scores for the class were no different from previous classes. It is difficult to determine exactly what impact the technologies may have had on Step 1 performance since many students also purchased and likely used printed texts to study and prepare for exams. Nevertheless, the integrated, technology enhanced curriculum at least did no harm to their overall learning of the material.

Although student and faculty opinions about the use of and satisfaction with technologies can provide useful information, the research needs to move forward to provide educators the knowledge of when to use technologies and how to use them effectively. E-learning research has demonstrated its effectiveness when compared to no intervention and similar effectiveness when compared to more traditional teaching methods.20 Studies that determine the effectiveness of new technologies should be conducted for any new technology that may enter the medical education environment. In additional to the other studies already mentioned, qualitative studies may need to be conducted to better understand the use of electronic textbooks as compared to traditional textbooks for both faculty and students.

Overall, the tablet PCs, video podcasts and electronic textbooks were well received by both students and faculty and the technology tended to enhance the learning environment. Based on feedback from students and faculty, plans for future classes include the use of tablet PCs, note taking software, a learning management system, virtual microscopy and podcasting. Students will continue to have access to web-based electronic textbooks through the library and will have the option to purchase electronic textbooks from publishers. Essentially these technologies have extended the learning space beyond the lecture hall, small group rooms, and laboratories by allowing students unlimited access to the material. Although the technology was well received, this current generation views technology as a tool to reach a desired outcome.2 As such, technology should be used if it can enhance the learning of the educational objectives as was recently demonstrated in a course designed to enhance team processing skills.21 As medical educators, we should be asking ourselves what we are doing to engage our students to develop the knowledge, critical thinking and reasoning, interpersonal communication skills, professional and ethical attitudes, and good judgment in evaluating and using online information necessary to become successful physicians. If current and emerging technologies can enhance the learning and acquisition of these important characteristics, then we should embrace them because our students have.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sandars, J., and Morrison, C. What is the net generation? The challenge for future medical education. Medical Teacher. 2007; 29: 85-88.

2. EDUCAUSE Oblinger, D.G., and Oblinger, J.L. Educating the net generation. EDUCAUSE e-Book; 2005. www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen [Accessed May 15, 2008].

3. Cook, D.A. Where are we with web-based learning in medical education? Medical Teacher, 2006; 28: 594-597.

4. Cook, D.A., Levinson, A.J., Garside, S., Dupras, D.M., Erwin, P.J., and Montori, V.M. Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008; 300: 1181-1196.

5. Letterie, G.S. Medical education as a science: the quality of evidence for computer-assisted instruction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003; 188: 849-853.

6. Valcke, M., and De Wever, B. Information and communication technologies in higher education: evidence-based practices in medical education. Medical Teacher. 2006; 28: 40-48.

7. Embi, P.J., Biddinger, P.W., Goldenhar, L.M., Schick, L.C., Kaya, B., and Held, J.D. Preferences regarding the computerized delivery of lecture content: a survey of medical students. Proceedings of the American Medical Informatics Association Annual Symposium on Biomedical and Health Informatics, 2006 Nov 11-15, Washington, DC.

8. Maag, M. Podcasting: An emerging technology in nursing education. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2006; 122: 835-836.

9. Billings-Gagliardi, S., and Mazor, K.M. Student decisions about lecture attendance: do electronic course materials matter? Academic Medicine. 2007; 82: S73-76.

10. Morton, D.A., Foreman, K.B., Goede, P.A., Bezzant, J.L., and Albertine, K,H. TK3 ebook software to author, distribute, and use electronic course content for medical education. Advances in Physiology Education. 2007; 31: 55-61.

11. Microsoft OneNote. Redmond, Washington: Microsoft Corporation; 2003 & 2007.

12. Agilix GoBinder. (www.gobinder.com). Orem, Utah; Agilix; 2007.

13. Angel Learning Management Suite 7.2. (www.angellearning.com). Indianapolis: Angel Learning; 2007.

14. AccessMedicine. (www.accessmedicine.com). McGraw-Hill Education; 2007.

15. VitalSource. (www.vitalsource.com). Raleigh, NC; VitalSource, 2007.

16. Aperio. (www.aperio.com). Vista, CA; Aperio Technologies, 2007.

17. Vovici. (www.vovici.com). Dulles, VA; Vovici; 2007

18. SPSS, SPSS base 15.0 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS, Inc; 2006.

19. Microsoft Excel. Redmond, Washington: Microsoft Corporation; 2003.

20. Cook, D.A. The failure of e-learning research to inform educational practice, and what we can do about it. Medical Teacher. 2009;31: 158-162.

21. Carbonaro, M., King, S., Taylor, E., Satzinger, F., Snart, F., and Drummond, J. Integration of e-learning technologies in an interprofessional health science course. Medical Teacher. 2008; 30: 25-33.