ABSTRACT

Health science educators are under increasing pressure to reduce traditional lecture time and build more interactive teaching into curricula. While small group exercises such as problem based learning achieve that aim, they are highly faculty intensive and difficult to sustain for many faculties. The commercial availability of easy to use audience response systems (ARS) provides a platform for increasing instructor interaction and engagement with learners. This article details my recent experience with ARS, and suggests its uses to increase lecture interactivity, build student teamwork, provide formative feedback, and energize both faculty and students.

INTRODUCTION

Recent medical education trends have emphasized the importance of increasing active learning for health science students. This trend has been driven by education literature emphasizing active learning, application, and analysis, rather than just memorization of facts, and by accreditation bodies1. Most education innovations have focused on adding new interactive techniques to curricula, such as problem-based or team-based learning, or use of standardized patients and simulations in small group exercises. Less attention has been given to how the traditional lecture might be enlivened and made more interactive.

For the past two years I have used an audience response system (ARS) in my core lectures in a second year required course in renal pathophysiology. My use of it was based on extensive literature, mostly from the undergraduate curriculum, touting ARS as a useful and stimulating addition to traditional teaching2. Among the advantages cited by these and other authors, I was most intrigued by these possibilities:

- Formative assessment that assess students’ understanding of my lecture material

- Stimulating students to apply and analyze, not just memorize

- Posing questions that demonstrate students’ gaps in knowledge and set up subsequent lecture material

- Providing a template for interactive discussion between students and between students and the instructor

- Providing guidance for the instructor to see if topics are understood, or require additional time in the lecture

- to make lecture fun

In this paper, I report on both my impressions and experience using ARS, and provide student feedback on the experiment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The ARS system used is the Interwrite PRS System, version 4.4 (Scottsdale, AZ). The system was used in a second year renal pathophysiology course in 2007 during a series of lectures on fluid and electrolyte disorders. Seven hours of lectures were given, and 20 ARS questions were asked during the lectures. Attendance at the sessions ranged from 35-60 students. Questions were delivered in one of two formats. In the first, a multiple choice single best answer or multiple best answer question was shown, and students were given 1-2 minutes to respond individually. After showing the class’ pooled responses graphically, I asked students who answered various responses to defend their answers, and then elaborated, asked follow up questions, or resumed lecture. In the second protocol, I asked students to discuss the question with nearby students after they saw the initial class response data. This discussion usually lasted 2-3 minutes. Students then re-entered their responses individually without comment from me. I then discussed the answers as above. Eight of the 20 ARS questions used in this report used the student discussion protocol, while 12 used individual student reporting only.

Student attitudes about ARS were surveyed in two ways. Routine end of course surveys were done on overall assessment of value, and the 54 responses were gathered by web based surveying by our office of medical education. Since class size was 94, this represents 56% of students. It is unknown how many ARS sessions were attended by these respondents. All likely attended at least one, since a possible option was “did not attend an ARS session”.

In addition, I surveyed students about their preferences of ARS learning vs. other modalities, and about their more generalized impressions, by use of ARS surveys done in class at the end of the series of lectures. Depending on attendance and participation that day, these ARS surveys yielded 40-46 responses.

RESULTS/DISCUSSION

ARS as Formative Assessment

A weakness of traditional lecture is its disengagement from a given class’ and individual learners’ specific needs. The lecturer often exists in a bubble, delivering the same content regardless of context. Since students may have varying learning styles, daily curricular schedules, and degree of fatigue, greater instructor awareness of their comprehension and attention can lead to more stimulating and focused learning sessions. This sensitivity to learner needs increases learner attention and involvement.

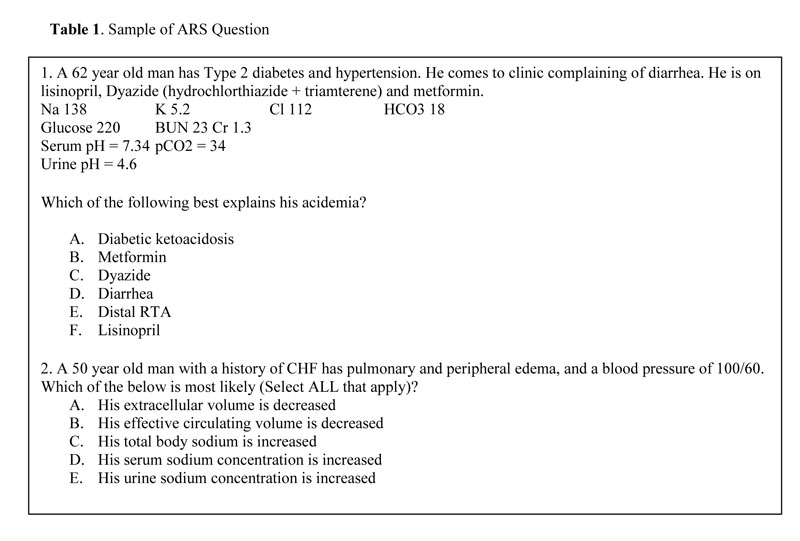

ARS questions are very useful here as the punctuation of a lecture segment, in order to assess student comprehension. In order to do so, the questions should be conceptual, asking learners to apply principles given in the lecture block, and not simply ask them to recall a specific fact. Such questions are best done in the form of experimental or clinical vignettes, as is now done in USMLE licensing examinations. See Table 1 for examples of this type of ARS question. As discussed below, if ARS reveals that students have not mastered the concept, a lecturer may need to spend additional time on it, rather than moving on in a fixed schedule. For example, question 1 requires learners to synthesize the preceding hour of material on different types of metabolic acidosis, using the vignette and lab values to classify the disorder, and engage in two step thinking in identifying a cause of the identified disorder (here, non anion gap metabolic acidosis with hyperkalemia). Many students missed this question, and further questioning of them revealed many cognitive problems, including focusing on only one value or vignette item, lack of a systematic analysis of the acid base disorder, and reliance on memorized lists rather than global analysis. The time spent on this question, in which I modeled my approach to its solution, gave students a framework for success in solving these problems.

ARS in stimulating knowledge application and analysis

The lecture has traditionally been the reservoir of facts. Most books and presentations on “Powerpoint® Technique” emphasize clarity and presentation of bullet point slides, on an assumption that data presentation is the main objective of any lecture. Textbooks are usually written in the same manner–comprehensive and organized coverage of facts is the most common structural underpinning of most medical and science texts. But should this be the purpose of a lecture for our students? Secondary school teaching typically is far more interactive, even in groups of 30-40. It is only on arrival to college that we treat the students to the one-way lecture, on the assumption that this is somehow preferred for these mature learners. It is certainly efficient. But even mature learners need to be motivated, stimulated, and challenged to move beyond the Bloom cognitive process of remembering to that of understanding, analyzing, and applying4. This should be our goal for students entering the complex synthesis that characterizes clinical care, and these skills must be rehearsed before intensive clinical care begins.

The expert teacher must reach many types of learners, including those who first need the facts, as well as those who want the facts presented conceptually and contextually. ARS can effectively facilitate such a learning system. Students can be provided a well written text or syllabus that lays out the facts clearly, and introduces terminology. Then, the ARS “lecture” can follow up with explanation, explication, and exemplification. Students often state in course evaluations that they benefit most from these sessions if they have read the facts first, so that they can come to the ARS session ready to extend their knowledge.

The ARS questions, if written to emphasize understanding and application, give students an idea of the level of knowledge expected by the instructor and guide their subsequent study away from rote memorization. To do this, I feel it is important that the questions be challenging, so students are motivated to review and learn more after the session (see Table 1). My ARS questions are a mix of single best answer and multiple best answer, and the students’ average correct response rates for each type in 2007 was 63% and 60%, respectively. Beginning or more insecure learners might benefit from less difficult questions that simply confirm memory of facts, but since I use these ARS sessions primarily to stimulate higher cognition, I feel that providing a false sense of mastery with easy questions undercuts the goal of motivating further study and self directed learning.

The use of clinical or experimental vignettes, amplified with the active learning of clicking on answers in the ARS format, can reformat the “lecture” into truly interactive learning session in which students extend their factual knowledge into application and analysis, and set the stage for deeper learning at home. If one therefore reconsiders what a “lecture” is, then the pressure to cover all the factual material disappears. In this model, the lecture is an active, energizing supplement to the written syllabus or text.

ARS for formative feedback (to students and instructor)

Students commonly complain that lecturers assume knowledge that is either more or less advanced than their actual level. Since effective learning occurs best when built upon a base of preexisting understanding5, the effective lecturer should assess this base regularly. This can be done in advance by reviewing the students’ prior curriculum and the specific content of preceding lectures. However, ARS offers the advantage of real time assessment of student preparation and understanding. Normally this is done by an assessment question at the end of a lecture segment, ideally spaced about 20 minutes after a similar question, in order to minimize student lapses in concentration. However, an ARS question can also be used to begin a lecture segment, showing students what they do not know and provoking interest in the upcoming segment. This is especially useful if students have already “covered” a topic in a previous course or lecture. The question can frame how their knowledge will be extended, not just repeated, in the succeeding minutes. In this use of ARS, it is not necessary that students successfully answer the question. In fact, I frequently do not discuss the correct answer after showing the response. Instead, I mention that the upcoming lecture segment will clarify the issue, and generally return to the question later, either as a lecture slide, or as a re-take of the question by the class. To summarize, ARS provides useful formative feedback for instructors and for students. For students, it joins end-of-syllabus chapter review questions and online exams as ways for my students to practice challenging questions of the type that I will ask on summative exams.

ARS as a vehicle for student peer interaction

The most common way in which ARS is used is the sequence: lecture -> ARS question -> answer -> instructor explanation. While engaging, this still keeps most students in a passive role. After reflecting on team-based learning strategies6-8, I now often use the ARS system to stimulate student-student interaction. After having students individually answer the ARS question, I show them the class distribution of answers, without indicating the correct answer. Then I ask them to discuss their answer with nearby colleagues for 1-2 minutes, and then individually re-enter their answer. Students usually respond more accurately after such discussion (improving their correct response rate by 2-10%), even when the correct answer was initially a minority response. Perhaps additional reflection time improves response, or perhaps students with better understanding are persuasive in the brief interactions with their colleagues. In any case, students gain the satisfaction of benefiting from peer interactions in improving their own understanding. If students self-correct, I frequently offer little additional explanation after the peer discussions, since the students have gained understanding on their own. Most students enjoyed the addition of peer discussion to the ARS sessions, but this is variable: 49% preferred student-student interaction, 27% preferred individual ARS use alone, and 24% were undecided (n = 41). Thus ARS can provide a collegial learning process that echoes some goals of problem-based learning9, 10 but now with a large class.

ARS for instructor feedback

A limitation of the lecture/transmission mode of teaching is its lack of real time feedback from learners. The lecture may have been delivered, but did learning occur? Traditional questions posed by the lecturer to the students often prompts more extroverted or knowledgeable students to respond, but this may not reflect the knowledge or engagement of the group as a whole. ARS provides an ideal medium to improve this student feedback to instructors (a vivid anecdote from a course in embryology teaching gives testimony to the lessons learned when student understanding is actually assessed)11. Regular use will tell the instructor whether points made were absorbed and understood. Low correct response rates on questions prompt the conscientious instructor to rephrase, repeat, or exemplify the poorly understood concept, so that learning occurs in the teachable moment. This inevitably “slows down” the lecture and may require the instructor to reduce the number of slides presented. However, if the traditional lecture is to be transformed into an interactive learning session, this “problem” is a good thing. Our students often complain that instructors may show in excess of 60 slides in a 50 minute lecture, and one lecturer at my institution has 120 scheduled for such a presentation. The feedback provoked by ARS can provide a needed brake on such excess.

ARS to make lecture fun

While learning should not be primarily an entertainment, enjoyment certainly belongs in any learning session. Humor, visual props, colorful slides, and animations are frequent lecture props, used by even traditional speakers to enliven the proceedings. However, these still remain mainly one-way, transmission oriented devices, in which the students remain observers, albeit more amused observers. ARS offers a platform for true interaction with students within the learning session, and provides a real sense that the teacher is interacting with learners, not just talking to them. This human contact allows a more personal interaction, even with a large group of students, and is a strong attractant for students who value the human interaction as key to learning (e.g. students with strong F domain in the Myers Briggs type indicator)12. Such students are often most put off by traditional lectures.

Limitations and Challenges of ARS

ARS is not an end in of itself. It is simply a new technological innovation that, if used well, can achieve the above aims. I list below several ARS pitfalls that should be avoided so that ARS does not detract from learning.

1. Overuse: One lecturer recently substituted ARS questions en bloc for his traditional lecture slides, without providing students with preliminary content via readings or other media. While the intent of session interactivity was appreciated, the students were made to answer ARS questions with only very limited knowledge, and resented the frustration of not being able to consolidate knowledge appropriately. Students surveyed after my ARS sessions strongly felt (92%, n=54) that three questions administered per 50 minute lecture was an ideal frequency, with the remainder evenly divided between wanting more and wanting less. They also felt that ARS works best on a base of factual knowledge, allowing them to explore its applications in a medical environment.

2. Overload: ARS cannot be grafted onto an already loaded slide presentation. Each slide takes 2-3 minutes at minimum, given the time to answer the question and to discuss the results. This often extends to 5 minutes or more. Obviously, pre-existing slides must be deleted to accommodate this, unless the session is lengthened, a rarity in the current minimalist lecture environment. This means that the instructor must prioritize the lecture content, using ARS to teach fewer concepts more deeply. Teaching fewer things with more depth, however, is a goal of most experienced teachers and leads to greater retention and application5.

3. Poorly written questions: In order for ARS to best provoke and stimulate students, questions should contain uncertainty, controversy, or analysis/application of material. Simple factual recall questions do not do this well. For my second year medical students I use questions similar to, or more advanced than, USMLE Part I questions (Table 1). These are normally based on experimental or clinical vignettes that provoke the students to analyze and apply their knowledge. This approach has the additional advantage of preparing students for the more analytic questions ideally used on summative course and licensing examinations.

4. Inadequate faculty development: The availability of an ARS system usually leads to initial administrative and student enthusiasm, typically because it is first used by the extroverted “early adaptor” instructor who infuses it with excitement13. Once the glowing initial reviews come in, other instructors may use it, but sometimes without any real preparation or orientation other than on the technical aspects of building the session. This often leads to the above listed mistakes, or a stylistic discontinuity in which a lecturer uses ARS questions but does not really engage the students verbally or emotionally. Students may then pan the entire technique. To avoid this drawback, our school provides regular lunchtime seminars for interested instructors in which experienced ARS users share tips and demonstrate effective practice. In addition, we have begun demonstrating ARS to entire departments at their faculty meetings so that all instructors can learn about ARS, thus enlivening a departmental course lecture curriculum systematically. Several initially reluctant instructors have told me that ARS helped them emerge from behind the podium and better engage the class, and improved their lecture technique generally. In these cases the technology facilitated a change in instructor behavior.

Student Response

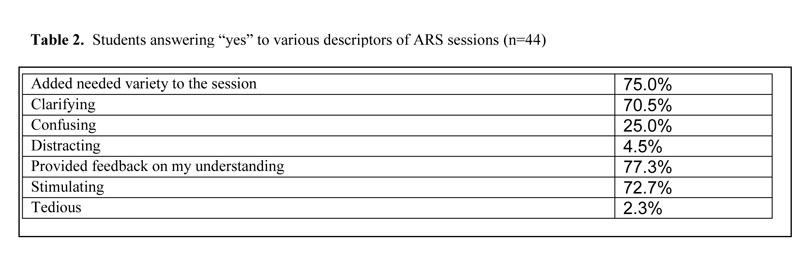

These second year medical students rated the educational value of ARS questions highly (6.8 out of a 7 point score, n=54). More affective responses are quantitated in Table 2. Post course comments indicated that individual students valued different types/uses of ARS questions:

“The audience response system is great for gauging our comprehension of materials just presented, and helps to further cement our newly acquired knowledge by making us recall and actively apply it to complex scenarios. I think it’s awesome!”

“(The instructor) uses it the way it was meant to be used. He goes over the concepts and then puts a little twist into a question and then we can discuss it.”

“I liked that he didn’t give us a question about something we haven’t seen yet.”

We are currently doing a systematic study of faculty lecture evaluations pre- and post- incorporation of ARS to further assess this issue. ARS may also motivate greater student attendance (this is not required at my university). Lecture attendance in my course, which has declined for the past several years, subjectively increased this year (no precise data available). While it is not clear that this trend, if verified, is due to ARS alone, others have reported increased learner participation rates with institution of ARS14. Overall student exam scores have not changed with use of ARS, but the course already had a rich assortment of sample questions for students to use, so this is not surprising.

CONCLUSION

While no technology serves as a panacea for indifferent or poorly prepared instructors, appropriate use of ARS increases interactivity in large group learning sessions. It joins team-based learning as another formal option for instructors who feel that their sessions need to become more interactive. The reduction of formal lecture time has been encouraged by many accrediting bodies such as LCME, but should not be done for that reason alone. Declining student attendance at lectures nationwide shows that students are increasingly needing a rationale for attendance, and if not given one, will choose a distance learning strategy. In my view, given the wealth of current online and written resources for students, this is a justifiable view. Any time used for whole class presentations should have a clear rationale beyond simple presentation of facts, which can be done effectively at home. Is a lecture that duplicates preexisting written materials worth the time? Audience response systems is one means of taking a large group session to a more stimulating, interactive level, and provides a format for professional faculty to re-engage with students and return to the art of teaching, not just lecturing.

REFERENCES

- Kassebaum, D.G., Cutler, E.R., Eaglen, R.H. The influence of accreditation on educational change in U.S. medical schools. Academic Medicine. 1997;72:1127-1133.

- Caldwell J.E. Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best-practice tips. CBE Life Scientific Education. 2007;6:9-20.

- Knight J.K., Wood, W.B. Teaching more by lecturing less. Cell Biology Education. 2005;4:298-310.

- Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R. (eds.). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York,NY: Longman.2001.

- Bransford, J.D., Brown, A., Cocking, R.R. (eds.). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington,D.C:National

Academy Press.2000. - Michaelsen, L.K. Team-based learning for health professions education : a guide to using small groups for improving learning. 1st ed. Sterling,VA:Stylus Publications.2008.

- Koles, P., Nelson, S., Stolfi, A., Parmelee, D., Destephen, D. Active learning in a Year 2 pathology curriculum. Medical Education. 2005;39:1045-1055.

- Nieder, G.L., Parmelee, D.X, Stolfi, A., Hudes, P.D. Team-based learning in a medical gross anatomy and embryology course. Clinical Anatomy.2005;18:56-63.

- Albanese, M.A, Mitchell, S. Problem-based learning: a review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Academic Medicine.1993;68:52-81.

- Norman, G.R., Schmidt, H.G. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: a review of the evidence. Academic Medicine. 1992;67:557-565.

- Wood, W.B. Clickers: A Teaching Gimmick that Works. Developmental Cell 2004;7:796-798.

- Bayne, R. The Myers-Briggs type indicator : a critical review and practical guide. London:Chapman and Hall.1995.

- Gladwell, M. The tipping point : how little things can make a big difference. 1st ed. Boston:Little, Brown.2000.

- Homme, J., Asay, G., Morgenstern, B. Utilisation of an audience response system. Medical Education. 2004;38:575.