ABSTRACT

Learning community models for medical student education are becoming an increasingly popular method to teach students clinical skills, provide appropriate mentorship, and foster medical professionalism. This paper describes the conception and implementation of such a model, called the Societies Program, at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. Incoming students are assigned to one of a highly selected group of experienced clinical educators in groups of 5 to 6 students, who remain together throughout medical school. The Societies Program introduces medical students to clinical medicine starting on the first day of medical school. Subsequently the groups meet for one afternoon per week in years 1 and 2 for a variety of clinical experiences including clinical labs, bedside teaching sessions, and personal and professional development sessions. These activities are closely linked to and integrated with the material being taught in the basic science blocks to facilitate integration of clinical and basic sciences. Within these sessions student clinical and professional skills are evaluated with a variety of competency-based formative and summative tools. All student work and reflections are compiled in an electronic portfolio designed to encourage self-reflection and student-driven learning.

Two years of data show that the Societies Program is highly valued by students and Society Mentors. This paper describes the challenges and successes encountered as the program started. More work is needed to evaluate the outcomes of this and similar programs. We hope this paper provides insight to those schools that are planning to develop or modify similar programs.

INTRODUCTION

Many medical colleges frequently assess and evaluate their curricula to determine what changes may be needed to better prepare medical students during their undergraduate years. However, schools typically focus on changing a single aspect of the curriculum until it is determined another curricular change is necessary.1-5 In 2005, the Dean of the University Of Arizona College Of Medicine (U of A COM) started an initiative to update and revise the entire four-year curriculum, starting with years 1 and 2. Literature searches reveal few US medical schools have implemented such a total transformation.6,7 Major changes occurred at every level of the curriculum, inclusive of but not limited to changing to a block format schedule, integrating basic science and clinical content into an organ systems approach, changing teaching and student performance assessment methodologies, increasing the number of basic science and clinical faculty for teaching and facilitating, and restructuring the clinical training in years 1 and 2. Curricular change is ongoing and the new clinical curriculum for years 3 and 4 recently began in July 2009. This paper reviews the design, implementation and lessons learned from one unique curricular aspect added to the new curriculum, the Societies Program. The Societies Program is based on the learning community model and is responsible for clinical training in years 1 and 2 and mentoring for all four years of medical school.

Review of the literature

Goldstein et al review the status of clinical skills education and the design and implementation of their Colleges Program at the University of Washington in their manuscript.8 The Learning Communities Institute at the University Of Iowa Carver College Of Medicine provides an updated listing of all of the learning communities at medical schools.9 There are currently sixteen learning communities at US medical schools included in this listing. The first began at the University of Iowa in 1999 with medical schools continuously adding new learning communities. All receive funding through their Dean offices and state budgets with one being funded by a private foundation. Some have dedicated physical space, while others share existing teaching space in the medical school. In addition to clinical skills instruction, there are mentoring activities, career advising, service-learning projects and discussions of the humanities, cultural competency, professionalism and the social sciences. Nearly half of them have a formal evaluation plan in place. One common theme is that faculty involvement is reserved for those faculty members with a reputation for excellence in education. Learning communities, including an on-line learning community, have also been used in nursing education.10-13

MATERIALS AND METHODS

a.Background information

After a thorough evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the medical school curriculum, in 2005 the Dean of the COM initiated complete revision of the pre-clinical curriculum at the COM, which had not changed substantially since the COM opened in 1967. The Dean cited many reasons for the change, including well documented and publicized reports on medical error such as those from the Institute of Medicine, changing societal needs, continually advancing and expanding medical knowledge, educational advancements and the increasing role of interprofessional collaboration in the care of patients.14,15 Along with changing from traditional longitudinal courses to a quasi-organ systems based approach, it was decided to revise the clinical training that COM students received during years 1 and 2. The COM previously relied on volunteer community and university-based preceptors for clinical training in the first two years. As such, there was great heterogeneity among the clinical experiences the students experienced. Citing the lack of a standardized clinical experience in years 1 and 2, the nation-wide decline in bedside teaching and longitudinal mentoring for students and the need to better integrate basic science and clinical science principles in the curriculum, the Dean proposed a learning community model to introduce students to concepts of professionalism and clinical competence early in their training.16,17 The goals of this learning community were: 1) longitudinal professional and clinical mentoring; 2) increased experiences in bedside teaching; 3) greater development of physical exam and medical interview skills; 4) greater development of clinical thinking and medical communication skills; 5) clinical application of basic sciences principles; and 6) consistent and structured exposure to modern concepts of medical professionalism.

b.Brief overview of the change from discipline to systems approach

A Steering Committee appointed by the Dean was charged with forming and staffing committees to design and transition the new basic science curriculum. The traditional longitudinal content (Year 1: Anatomy, Histology, Neurosciences, Physiology, Biochemistry, Medical & Molecular Genetics, Medical Interview & Physical Exam; and Year 2: Pathology, Pharmacology, Microbiology, Clinical Correlations with Pathology, Clinical Preceptorship) was redesigned into an integrated block structure. The Blocks are: Prologue (1 week); Foundations; Nervous System; Musculoskeletal System; Cardiac, Pulmonary and Renal Systems; Digestion, Metabolism and Hormones; Life Cycle; Infection and Immunity; Cancer; and Advanced Topics. In addition to traditional content, curricular threads were woven throughout the blocks (Aging, Evidence-Based Decision Making, Gender-specific Medicine, Health and Society, Humanism, and Interprofessional Education). New teaching modalities introduced include interactive lectures, case-based instruction, team-based learning, and interprofessional exercises shared with the Colleges of Law, Nursing, Pharmacy and Public Health and the School of Social Work.

c.Planning for Society program

After the Dean confirmed that a learning community model was financially viable, he sent a faculty member to the University of Washington, a nearby school with an established learning community identified to have similar goals as those to which the COM aspired. Soon after, the Dean appointed the Director of the learning communities (0.75 FTE, also functions as Assistant Dean for Clinical Education), which was named the Societies Program. The director continued with a literature search, another visit to the University of Washington, and (with the Dean, the Vice-Dean for Academic Affairs, and the Senior Associate Dean for Medical Student Education) appointed three other Society Heads (0.50 FTE each). The Director also functions as a Society Head, for a total of four. The Society Heads continued work on the structure of the Societies Curriculum while accepting applications for the remaining Society Mentor positions. The faculty and student structure of the Societies Program was decided on: The Societies Program is comprised of four Societies (named after indigenous Arizona flora – Agave, Acacia, Cholla and Manzanita). Each Society has five clinical Mentors (including the Head) for a total of 20 Society Mentors. Each Society Mentor teaches and mentors a group of five to six students in each year of medical school. Although the group stays together for all four years, currently almost all the activities occur in years 1 and 2; Societies activities in years 3 and 4 are in evolution as the year 3 and 4 curriculum is being revised.

d.Selection of mentors

The Societies Director sent invitations to clinician educators to apply for the 19 open Mentor positions. The Societies Director also functioned as a Mentor and there are two additional back-up Mentors for the Program. The four Society Heads selected the remaining Mentors. It was a very competitive process and the most outstanding educators in the College were chosen to be Mentors. A formal application and interview process was utilized to select the Mentors. Applicants were asked to: (i) list medical student and resident teaching experiences, along with relevant educational, academic and employment background, including any teaching awards or honors; (ii) describe their philosophy of medical education as it pertains to the concept of the Societies Program; (iii) submit a letter of recommendation from a colleague attesting to the applicant’s skill and enthusiasm for medical education; and (iv) submit a form signed by the applicant’s department head expressing support for the application. The position of Society Mentor is 30% (0.3 FTE) of the physicians’ time; this includes two afternoons each week for teaching year 1 and year 2 students and one afternoon each week for faculty development. Each Mentor’s home department receives remuneration for the Mentor’s time. Clinician-educators in all disciplines were encouraged to apply; the initial group of Mentors included four general internists, nine family physicians, two pediatricians, two surgeons and three emergency medicine physicians.

e.Faculty development of mentors

The selection process was completed by January 2006. At that time the group began a series of weekly Friday afternoon meetings (four hours each) during the remaining six and one-half months until the start of the academic year. During these mandatory sessions the group developed, discussed, and reviewed all aspects of the new Societies’ curriculum. Faculty development for Society Mentors is an ongoing process and the Mentors meet each Friday afternoon for this purpose. Topics for discussion include debriefing of previously completed sessions, continued curricular development, basic science reviews and clinical topic reviews. The Societies Faculty has become a learning community as well and time is spent discussing both the educational and personal successes and the challenges and mistakes that Mentors have experienced during their teaching sessions.

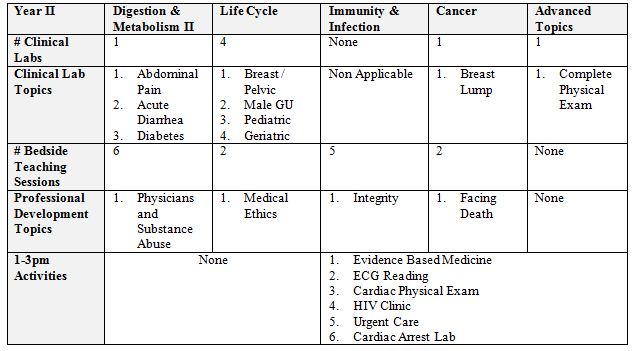

Table 2. Soceity’ Activities & Objectives

f.Society curriculum and The Doctor & Patient Course

Students meet with their Society Mentor and group for one afternoon each week. During the Foundations Block, the first full block, the curriculum is unique. In this nine-week block the Society Mentor teaches the medical student group the basic elements of the medical history and the normal physical exam. These sessions are split into two, two-hour sections, one focusing on the basic medical history (using hospitalized patients) and one focusing on the normal physical exam (using students under Mentor supervision). In the old curriculum the physical examination was taught to the first year students by fourth year medical students. Additionally, the high risk behaviors interview and delivering bad news are taught using standardized patients (SPs) during this block. With the anticipation of weekly four-hour bedside sessions, we were able to teach a more basic medical interview and physical examination segment. Students must complete an observed full history and physical at the end of the block. In subsequent blocks, the activities include Clinical Labs using standardized patients, Bedside Teaching Sessions, and Professional Development sessions (Tables 1 & 2).

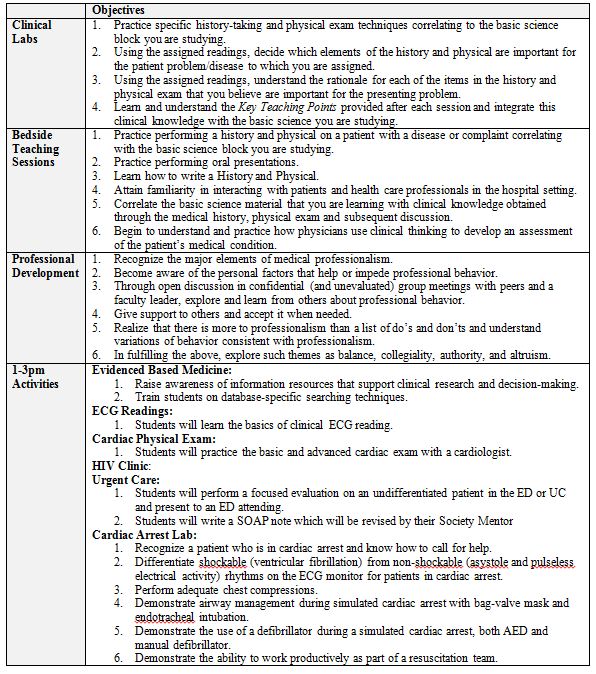

Clinical Labs occur once or twice within each basic science block. The objectives of the labs are to 1) teach advanced elements of the history and physical exam related to the basic science block the students are studying; and 2) to help students begin to understand which elements of the history and physical are most important for various complaints and the rationale for each of those elements. Students are assigned a clinical topic that is related to the block they are studying (Table 1). Each clinical topic includes reading sets on the appropriate medical history and a relevant chapter from Up To Date.18 Students perform a focused history and physical on a standardized patient with a complaint related to the clinical topic they were assigned while the mentor observes and grades the encounter using a mini-clinical evaluation (mini-CEX) checklist. (See Appendix 1) There are usually three different clinical cases utilized for each lab. After performing the focused H&P, the students present the case and their findings to the mentor and teach the remaining students in the group (who were assigned different cases) the most important elements of their reading sets (Tierney text and Up To Date). Finally, the Mentor distributes and goes over the key clinical teaching points that were developed for each case. (See Appendix 2)

Bedside Teaching Sessions are the core of Societies activities. Patients for these sessions are recruited the morning of the sessions by program Patient Coordinators at our teaching hospitals. Care is taken to recruit patients with diagnoses that relate (when possible) to the basic science the students are studying to maximize basic and clinical science integration. During year 1, one student per group per session is assigned to evaluate a patient and perform a history and physical examination (H&P), directly observed by his or her Mentor; another student in the group serves as a peer observer and evaluator. While Bedside Teaching Sessions are the core of Societies activities. Patients for these sessions are recruited the morning of the sessions by program Patient Coordinators at our teaching hospitals. Care is taken to recruit patients with diagnoses that relate (when possible) to the basic science the students are studying to maximize basic and clinical science integration. During year 1, one student per group per session is assigned to evaluate a patient and perform a history and physical examination (H&P), directly observed by his or her Mentor; another student in the group serves as a peer observer and evaluator. While this is occurring, the remainder of the group is assigned research relating to the patient’s diagnosis, assigned to practice a history and physical on a standardized patient in the teaching clinic, assigned to a formal ophthalmology lab, or assigned to another clinical activity. (See Table 1; section “1-3pm Activities”) After the student completes the H&P, the whole group reconvenes at the bedside to hear an informal oral presentation by the examining student and talk to and examine the patient. The group then proceeds to a small group teaching room, where further discussion about the case ensues, incorporating the research done by other group members. Mentors are responsible for integrating basic science and psychosocial issues as appropriate. Formal timed oral presentations are then given for patient(s) seen the week before, and Mentors review write-ups that were turned in the previous week. Formative feedback is given to the students at each session by both their Mentor and their peers in the group. During year 2, two students from each group perform a history and physical exam, with the mentor splitting direct observation time between the two students. In year 2, peer observers/evaluators are not used: Year 2 students who are not performing the H&P participate in the following activities on a rotating basis while waiting for the group to reconvene at the bedside: ECG tutorial, the advanced cardiac examination lab, an urgent care experience, pelvic exam lab, evidence-based decision making tutorial, HIV clinic, cardiac arrest lab (using a simulator) and other activities. (See Table 1; section “1-3pm Activities”) Case discussions during year 2 incorporate clinical thinking exercises whenever possible.

Personal and Professional Development (PPD) Sessions (previously called Professional Development sessions) focus on issues related to medical professionalism, ethics, death and dying, student well-being, and related topics (Table 2) in order to broaden student knowledge of the intricacies involved in doctoring and self-care during the educational process. These sessions occur periodically through the year, often on exam weeks, as these sessions take less time than the regular Societies activities and require no student preparation. Each session is introduced by a 30-minute talk on the chosen topic. Following this, students break into their groups to discuss these issues with their PPD Mentor as it relates to them professionally and/or personally. Student support and personal disclosure are optional components of these sessions. To assure separation of counseling and evaluative functions and to encourage free discussion, the students’ PPD Mentor is different from their regular Society Mentor. All PPD Mentors are Societies faculty and remain with the same group for the two-year period. If a PPD Mentor senses a student is having emotional or academic issues, he or she refers the student to the appropriate COM resources.

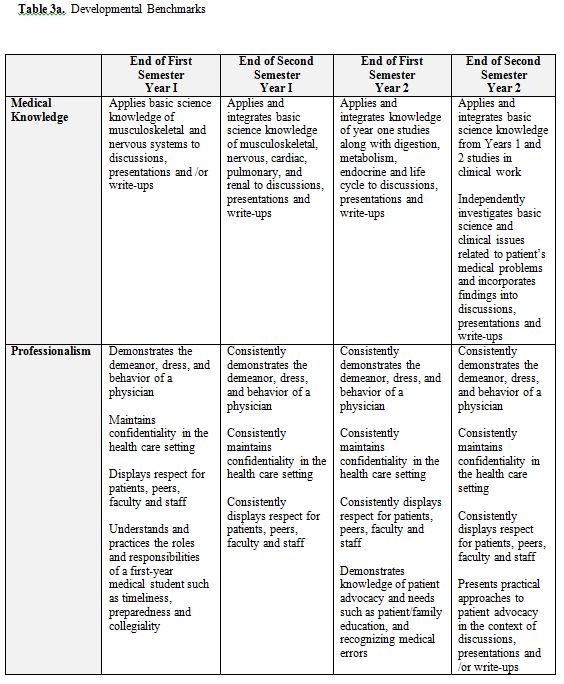

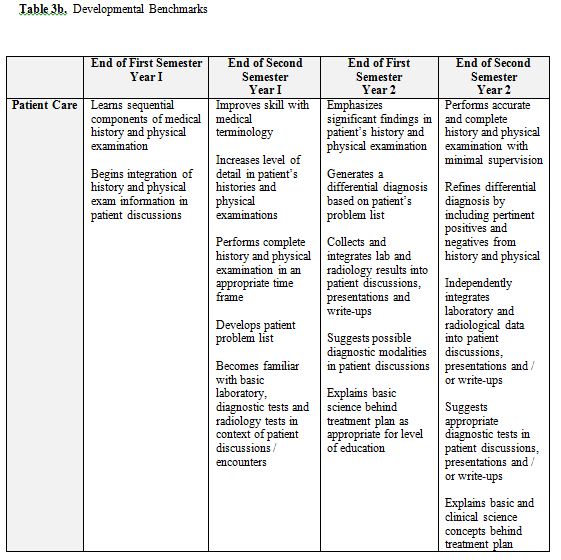

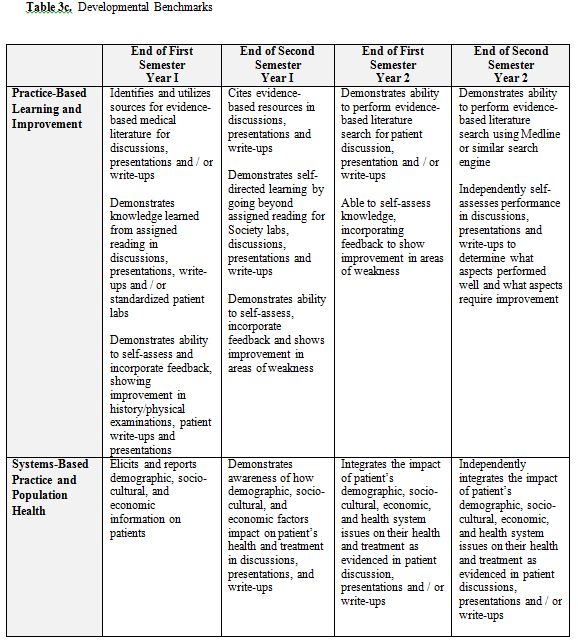

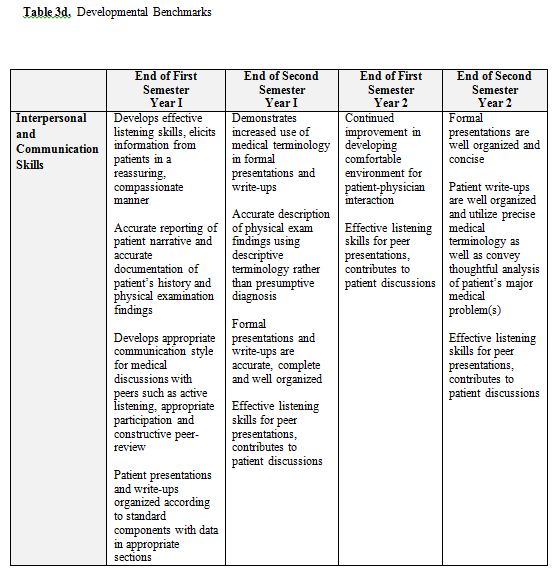

The Doctor and Patient Course is a longitudinal clinical skills course that spans the first two years of medical school. The course is the objective part of the Societies Program and is administered by the Society Mentors. The specific components include those that are woven into the sessions described above plus other activities. Formal interactive lectures are given for the following topics: writing SOAP notes and H&Ps, oral presentations, and clinical thinking. Materials developed by Society Mentors specifically for these sessions are used. During the Clinical Labs, students are graded on their overall performance using a mini-CEX checklist that contains the elements of the history and physical that the students should be asking or performing for each clinical problem in the labs. During the Bedside Teaching Sessions, the students’ interactions with the patients are critiqued using the Bedside Evaluation form. The students’ formal oral presentations are critiqued with another form designed specifically for this activity. Finally, the written H&Ps are graded in two ways: 1) the Mentors critique the actual content of the H&P electronically using Microsoft Word and “Track Changes/Insert Comment” tool; and 2) with an overall global H&P evaluation form. All of these evaluations and H&Ps are kept in an electronic portfolio (called the Society Portfolio) that is accessible to Mentors and students at any time. (See Appendix 3 for a sample Evaluation Form) Additionally, students are responsible for one reflective exercise per year, and these also are housed in the Society Portfolio. Each student’s overall performance is documented using a four-semester set of competency-based, developmental benchmarks (Table 3). Students and faculty independently fill out the benchmark form (the responses are then combined into a single electronic document) and compare results during Portfolio Reviews. Portfolio Reviews occur every semester; during these sessions students meet individually with their Society Mentors to go over their Benchmarks evaluation and the general progression of their clinical work. Based on this discussion, the Mentors help the students formulate specific goals and objectives for the coming semester. These goals are also documented in the Society Portfolio. Finally, OSCEs (Objective Structured Clinical Examinations) (described below) at the end of year 1 and year 2 serve as final examinations for each year of the Doctor & Patient Course.

Implementation

Implementation of the Societies Program would not have been possible without the steady support of the Dean of the COM and other key educational administrators. State funds earmarked for medical student education were used to fund the program, including the Society Director, Society Heads, Society Mentors, Program Coordinators, Patient Coordinators, and infrastructure. After the previously described initial six month faculty development, the Societies Program began in the fall of 2006 with the incoming class of 2010.

In the old curriculum, there was a 200-hour course entitled Preparation for Clinical Medicine (PCM). One of the Society Heads had been the Director of that course. Much of the material from PCM including the medical interview, physical examination, note writing, and clinical thinking was re-written and integrated into the Societies’ curriculum.

On the afternoon of the first day of medical school, the students meet their mentors and begin a short discussion about the structure of the Societies Program. After this brief introduction, the students accompany their Mentors to the hospital where the Mentors conduct an interview with patients while the students observe. In this interview the Mentors encourage the patients to discuss their experiences as patients, rather than a standard hospitalized patient interview. The only student objective for this session is for the “students to conduct themselves appropriately and professionally during an interview with a patient.” After this interview, the Mentors also encourage the students to converse with the patients. The group then adjourns to their small group room for a debriefing session during which the Mentors engage the students in a discussion of their experiences and reactions to the patient comments. The students begin their weekly patient encounters the following week with the start of the Foundations Block.

Our former curriculum included an extensive Patient Instructor and Standardized Patient program. We were fortunate to be able to continue using this outstanding resource. The SPs are broadly involved with the Societies/Doctor and Patient medical interview and physical examination segments. During the medical interview component, they assist with the interview and patient communication sessions designed to teach students how to inquire about patients’ high risk behaviors and how to deliver bad news; they also assist with the final sessions during which students’ conduct complete medical interviews. Additionally, they assist in the final examination for the physical examination segment. As described above, we have Clinical Labs in each block; SPs are trained to portray the patients for these labs as well. Finally, throughout the blocks during the bedside teaching sessions, some of the students who are not assigned to perform an H&P that week use this opportunity to practice the interview and physical exam with the SPs.

The University of Arizona COM has administered a high-stakes OSCE for over twenty years. Administered at the end of Year 3, passing this OSCE is a graduation requirement. With the advent of the new curriculum we added an end-of-Year 1 and end-of-Year 2 OSCE. These exams are shorter and less comprehensive than the original end-of-Year 3 OSCE. They have four stations and focus on the clinical cases that were presented during the Societies labs in each block. After the first administration of the Year 2 OSCE we redesigned it to allow for greater standardization in the evaluation system and to ensure that each of the students is prepared to begin their third-year clerkships. Our Year 2 OSCE now combines standardized patient cases with direct observation by a mentor and an oral examination administered by a mentor. With this new OSCE, each student sees two patients portraying a scenario with one of five common symptoms. The students perform a focused history and physical examination while a mentor (not their regular mentor) observes the interaction on a monitor in a separate room. After the student has a few minutes to collect his/her thoughts, the student and mentor meet in a separate room where the student makes an oral presentation of the patient followed by an oral examination aimed at assessing the student clinical thinking skills. The focus of this oral examination is not to assess content knowledge but rather the students’ diagnostic reasoning. All of the mentors spent at least four hours of faculty development sessions in order to standardize this oral examination. All of the cases portray

a common symptom with multiple possible diagnoses. To be successful, the student must perform a focused, yet thorough examination. The mentors target the oral examination not specifically on the diagnoses but rather on the signs and symptoms that would help lead to the diagnoses and the relative importance of those signs and symptoms in arriving at a diagnosis. Through this year 2 OSCE we achieve standardization of evaluation and assure that each student is ready to start clinical clerkships.

RESULTS

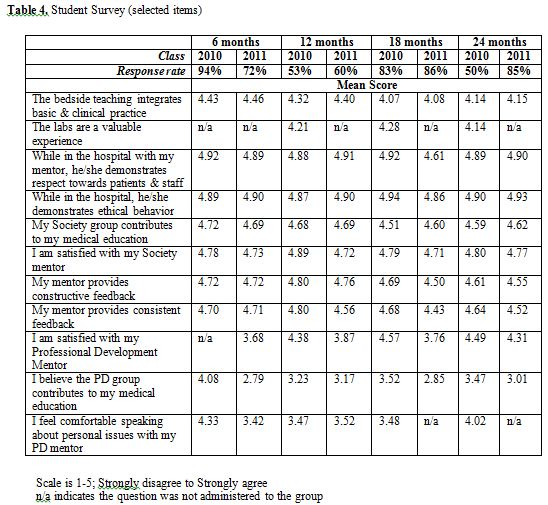

The Program Evaluation Team in the Office of Medical Student Evaluation administered multiple surveys to our students. The surveys questioned students about the bedside teaching, standardized patient labs and professional development sessions. Results of surveys collected at different times during the year are shown for the Classes of 2010 (first cohort) and 2011 (second cohort) in Table 4.

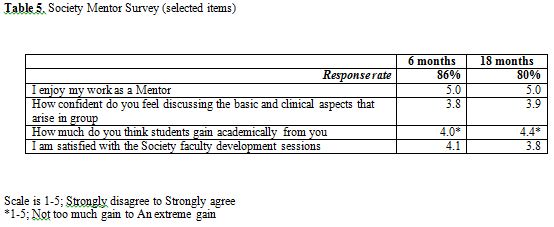

The Societies Program as a whole has received consistently high marks from students, who consider the program to be an instrumental part of their medical education. The first eight rows of Table 4 refer to core Societies clinical and mentoring activities. The average score for all these activities is above 4.5 on a 1 to 5 scale (5 being best). Rows 9 – 11 refer to the Personal and Professional Development Program that is housed within the Societies Program as described above. While acceptable, the average score for some of these items is noticeably lower than the core clinical activities. Core aspects of Society Mentor satisfaction surveys are presented in Table 5. The results confirm that all the Mentors enjoy their work in the program and feel they are contributing significantly to student education.

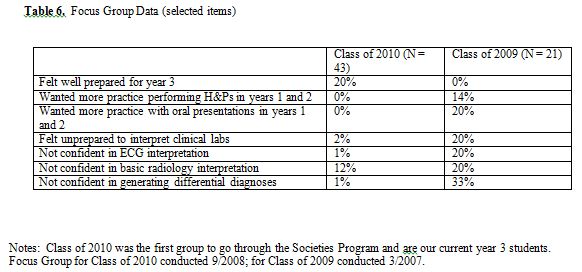

The COM has traditionally held focus groups with year 3 students to determine how prepared students felt as they started the clinical clerkships. In 2007, 21 members of the class of 2009 participated in the focus group; in 2008, 43 members of the class of 2010 (the first cohort to participate in the Societies Program) participated in the focus group. While none of the focus group participants from the Class of 2009 felt prepared to begin year 3 clerkships, 20% of the focus group participants from the Class of 2010 felt prepared. Likewise, the focus group participants from the Class of 2010 felt much more prepared to perform medical histories and physical exams, to present patients orally, to interpret objective clinical data (labs, ECGs), and to generate differential diagnoses (Table 6). While these focus group data are not conclusive, they provide preliminary evidence that the Societies Program prepares students for the year 3 clerkships more so than the previous community-based program.

DISCUSSION AND LESSONS LEARNED

While we believe the Societies Program has been very successful thus far, there have been many challenges during the implementation of the program.

- Identifying the appropriate level to teach the students. All of our Society Mentors are experienced clinical educators. However, while some had participated in previous clinical activities in years 1 and 2, most of the group’s educational expertise was in teaching clinical medicine to year 3 and year 4 students and residents. As such it was easy for Mentors to teach at a level higher than that for which the year 1 and 2 students were prepared, especially when integrating clinical and basic science in discussions. With student feedback, faculty development sessions and experience, Society Mentors feel they have greatly improved their ability to teach at the appropriate level, increasing the complexity as student knowledge and experience grows.

- Heterogeneity within the groups. While the Society leadership and mentors worked hard to standardize the activities as described above, it is not surprising that there are significant differences among the mentoring groups in how the sessions are run. These differences relate to several factors: Mentor specialty, Mentor personality, student/group personality, and Mentor organization/time management skills. Specifically, differences related to:

oTime. Although most sessions are scheduled from 1 to 5 PM, some groups end significantly earlier on a regular basis. This causes student angst on several levels: some students whose sessions end early feel they are missing out on potentially richer educational experiences while conversely some students whose groups always end at 5 PM feel they are being worked too hard.

oStudent feedback. While all students receive feedback, some groups provide more peer and/or faculty feedback than others. Not surprisingly, some students feel there is too much feedback while others feel there is not enough. As an example, an internal review of students’ H&Ps finds great variability in how many comments Mentors make when reviewing them.

oIntegration of basic science material. While all Mentors are encouraged to review the curriculum weekly for both year 1 and 2 and integrate this material into the sessions when applicable, some Mentors do this more than others. Additionally, some Mentors feel more comfortable with basic science concepts than others.

oIntegration of “thread” material (described above). Again, all Mentors are aware of the curricular “threads” and attempt to integrate these concepts into sessions when appropriate, but the extent to which each Mentor does this varies. Additionally, because there are multiple activities and goals for each session, little time is left to address “thread” concepts.

oSettings. Mentors with easy access to the Emergency Department, the operating room or an ambulatory clinic will at times use these settings for their groups. While adding welcome diversity to the experience for those students, students in other groups may feel left out. This is somewhat mitigated by the fact that most Mentors have access to at least one other clinical setting to use other than the hospital.

The Mentors addressed these issues related to heterogeneity through our faculty development sessions. We had open discussions regarding the pros and cons of the varied approaches and were able to build consensus, although this is an ongoing process.

•Competition with basic science effort. Although most students enjoy the clinical sessions and understand the importance of the sessions for their education, the stress of studying vast amounts of material for the basic science blocks can dull students’ enthusiasm for the Societies sessions. At times, Mentors feel that their students are not taking the time to prepare for the sessions. This perhaps is exacerbated by the fact that Societies sessions and the Doctor & Patient course are Pass/Fail, whereas the basic science blocks report final percentage grades for the Dean’s Letter.

•Maintaining interest and furthering student development. Because the first- and second-year Societies Program curriculum are similar with the primary difference being increased patient encounters in the second year, some students feel they have learned how to take an H&P by the end of year 1 and see little value in continuing to practice these essential skills. Assuring that students continue to advance their clinical and diagnostic skills necessitates students and Mentors to be equally aware of those areas in which students need improvement and to explicitly target those areas together.

•Problems with the Professional Development curriculum. Medical professionalism is known to be difficult to teach and discuss with pre-clinical medical students.19,20 We placed these interactive sessions during exam weeks, because the professional development sessions are significantly shorter than other Societies activities (two hours versus -four hours) and the sessions can be completed in one day scheduled early in the week rather than the two days required to complete regular Societies activities. In this way, all students have a smaller time commitment for Societies, which is completed early in the week allows more time to prepare for block examinations. None the less, some students complained about even this minimal commitment during exam weeks, and the overall student satisfaction for these sessions is lower than for other Societies activities (Table 4). Some students also objected to the content and the support function that is an optional part of these sessions. Still most students understand the purpose of the sessions and enjoy getting to know another Mentor. We will continue to develop this part of the curriculum with the hope of making the important topics covered in these sessions more aligned with the students’ current stage of professional development and thus more meaningful.

There have been many benefits that were not originally planned:

•Society Mentors forming their own learning community. Meeting for faculty development activities one afternoon almost every week has formed a learning community for the Mentors as well. Designing and participating in medical education-based faculty development and sharing our educational encounters have proven to be rich experiences for the Mentors. The Mentors previously knew of each other but never had the opportunity or the time to share meaningful educational experiences and ideas with each other. The educational experience and wisdom of the collective group is astounding and each Mentor feels privileged to be a part of this community.

•Identification of problem students early in training. Medical students with problems in professionalism or ability to interact appropriately with peers and patients usually do not come to the attention of the school until the clinical years, when it may be more difficult to remediate the student. Since one Mentor works with the same group of students every week for two years, he or she is able to observe their students in a variety of circumstances, some quite stressful. Issues relating to professionalism and aberrant interpersonal behaviors are usually apparent to the Mentors. As such the student can receive needed help early in their medical education.

•Students becoming comfortable with taking risks, being wrong, and participating in feedback. Although most groups start off tentatively, we have found that trust is soon established. As medical students are traditionally embarrassed to make mistakes and not comfortable giving meaningful feedback to peers, it is very gratifying to see students relax and freely learn from and give feedback to each other.

We chose to begin our students’ clinical exposure on the first day of Year 1 as described above. We also were aware of both the inherent appeal to students of participating clinical activities early in their education and the risks of engaging students in clinical work so early in medical school. The basic sciences curriculum is extensive and detailed. Although many believe a retreat to the hospital to be an important reprieve for the students deeply engaged in their basic science studies, we also recognized its potential peril. To address these concerns, we work closely with the basic science block directors to design the Societies Program to be as closely aligned to the block curriculum as possible. Our clinical labs work in parallel with the materials being learned in the classroom and whenever possible, the patients seen by the students each week had a diagnosis being studied in the classroom. As discussed above, the Year 1 students are assigned to perform H&Ps approximately half as often as the Year 2 students; we worked to make the curriculum developmentally appropriate by increasing our expectations of student clinical work each semester with both formative feedback and objectively with our Developmental Benchmarks. (See Table 3) As we noted above, this early initiation of clinical activity was well received by our students. Nonetheless, we are aware of the ‘hallway chatter’ and continuously elicit feedback from the students in an attempt to maintain an acceptable balance between the excitement of early clinical work and the potential distraction from student basic science studies.

We are confident that our group of twenty Mentors provides a learning experience that is significantly more standardized than that provided by our former greater–than-one-hundred group of clinical preceptors. However, even with our weekly faculty development, we are aware that teaching and feedback to the students varies from group to group. As discussed above, the revised end of Year 2 OSCE created the standardization of evaluation we sought.

CONCLUSIONS

We have shown that an intensive learning community model for clinical education and mentoring of 1st and 2nd medical students is feasible and acceptable to both students and faculty. The student evaluations place the Societies Program among the most highly rated components of our new curriculum and faculty evaluations demonstrate a high level of satisfaction with participation in the program. Aligning the program as closely as possible with the basic science blocks enhances relevance for students and encourages integration of basic and clinical science concepts. Preliminary data suggest that the Societies Program is more successful at preparing students for year 3 than our previous curriculum. The program is in continual development to enhance the applicability and developmental nature of the curriculum. Future study is needed to establish the value of such learning community models based on more objective outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Kathy Mendoza, PhD, for her role in administering, organizing and extracting survey data.

REFERENCES

- Distlehorst, L.H., Dawson, E., Robbs, R.S., Barrows, H.S. Problem-based learning outcomes: the glass half-full. Acad Med. 2005;80(3):294-299.

- Enarson. C., Cariaga-Lo, L. Influence of curriculum type on student performance in the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and Step 2 exams: problem-based learning vs. lecture-based curriculum. Med Educ. 2001;35(11):1050-1055.

- Hoffman, K., Hosokawa, M., Blake, R., Jr., Headrick, L., Johnson, G. Problem-based learning outcomes: ten years of experience at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2006; 81 (7):617-625.

- Moore, G.T., Block, S.D., Style, C.B., Mitchell, R. The influence of the New Pathway curriculum on Harvard medical students. Acad Med 1994;69(12):983-989.

- Wilkerson, L., Wimmers, P., Doyle, L.H., Uijtdehaage, S. Two perspectives on the effects of a curriculum change: student experience and the United States medical licensing examination, step 1. Acad Med. 2007;82(10 Suppl):S117-120.

- Loeser, H., O’Sullivan, P., Irby, D.M. Leadership lessons from curricular change at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2007; 82(4):324-330.

- Muller, J.H., Jain, S., Loeser, H., Irby, D.M. Lessons learned about integrating a medical school curriculum: perceptions of students, faculty and curriculum leaders. Med Educ. 2008;42(8):778-785.

- Goldstein, E.A., Maclaren, C.F., Smith, S., Mengert, T.J., Maestas, R.R., Foy, H.M., Wenrich, M.D., Ramsey, P.G. Promoting fundamental clinical skills: a competency-based college approach at the University of Washington. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):423-433.

- Medical Schools with Learning Communities. 2009. http://www.medicine.uiowa.edu/osac/Comminst/schools-table.html.) [Accessed March 17, 2010]

- Tilley, D.S., Boswell, C., Cannon, S. Developing and establishing online student learning communities. Comput Inform Nurs. 2006;24(3):144-149.

- Bassi, S., Polifroni, E.C. Learning communities: the link to recruitment and retention. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2005; 21(3):103-109.

- Churchill, J., Reno, B., Batchelor, N. The learning communities concept: increasing student involvement. Nurse Educ. 1998;23(6):7-8.

- Doty, E.A. Organizing to learn: recognizing and cultivating learning communities. Semin Nurse Manag. 2002;10(3):196-205.

- Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, D.C.: 1999.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: 2001.

- Mooradian, N.L., Caruso, J.W., Kane, G.K. Increasing the time faculty spend at the bedside during teaching rounds. Acad Med. 2001;76(2):200.

- Ramani, S., Orlander, J.D., Strunin, L., Barber, T.W. Whither bedside teaching? A focus-group study of clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78(4):384-390.

- Tierney, L.M., Henderson, M.C. The patient history: Evidence-based approach. New York: Lange; 2005.

- Krych, E.H., Vande Voort, J.L. Medical students speak: a two-voice comment on learning professionalism in medicine. Clin Anat. 2006;19(5):415-418.

- Goldstein, E.A., Maestas, R.R., Fryer-Edwards, K., Wenrich, M.D., Oelschlager, A.M., Baernstein, A., Kimball, H.R. Professionalism in medical education: an institutional challenge. Acad Med. 2006;81(10):871-876.

APPENDIX 1:ACUTE ABDOMEN MINI-CEX

Doctor and Patient: Integrating the Art and Science of Medicine

Mini CEX – DMH Block

CC: Acute abdominal pain

HPI:

Age of patient (very important in evaluation of acute abdominal pain):

1.O = Onset

a.When did the pain first start?

b.Onset sudden or gradual?

2.P = Position, Pattern, Location

a.Diffuse vs. localized?

3.Q = Quality (type of pain)

a.Dull, sharp, colicky, waxing and waning, etc.

4.R = Radiation

a.Back

b.Flank and groin

c.Shoulder

5.S = Severity (1-10)

6.T = Timing — high risk features include:

a.Sudden onset?

b.Maximal at onset?

c.Pain with subsequent vomiting?

d.Constant pain for Allergies / Adverse Drug Events:

Past Medical & Past Surgical History

1.prior abdominal surgery

2.cardiovascular disease

3.history of HIV infection

4.Obstetric history

Medications:

1.NSAID’s

Family History:

1.Cholelithiasis? nephrolithiasis?

Social History / High Risk Behaviors:

1.Alcohol consumption

2.Recent travel

Physical Examination:

1.General appearance

a.patients age

b.level of discomfort

c.motionless vs. changing position

2.Vital signs

a.orthostatic symptoms

b.tachycardia

c.fever

3.Eye exam

a. scleral icterus

4.Skin exam

a.jaundice

b.Abdominal or flank ecchymosis

5.Cardiac and vascular exam

a.atrial fibrillation

b.cardiac murmurs

c.abdominal bruits

6.Pulmonary exam

a.Consolidation at lung base

7.Abdominal exam

a.Observation

i.Distension

ii.Visible peristalsis

b.Two minute auscultation

i.Bowel sounds

ii.Aortic and femoral bruits

c.Palpation

i.Lightly for rigidity

ii.Deeply for localized tend.

iii.Palpation of aorta (older ♂)

iv.Carnett’s sign

v.Murphy’s sigh

vi.Psoas sign

vii.Obturator sign

viii.Rovsing’s sign

8.Pelvic exam

a.“I need to perform a pelvic exam.”

9.Testicular exam

a.“I need to perform a testicular exam.”

10.Rectal exam

a.“I need to perform a rectal exam.”

11.Extremities

a.Peripheral vascular disease?

Key Knowledge:

In the evaluation of acute abdominal pain is different from that of chronic abdominal pain, and includes several potentially life-threatening diagnoses. This session focuses on acute abdominal pain.

In evaluating acute abdominal pain, it is important to search for and exclude:

•abdominal aortic aneurysm

•mesenteric ischemia

•bowel perforation

•acute bowel obstruction

•volvulus

•myocardial infarction

In women of childbearing age, pregnancy status must be determined.

Three classes of abdominal pain:

•Visceral pain: innervation bilaterally at multiple levels; dull, poorly localized, felt in midline. Caused by ischemia, inflammation, or distention of hollow organs or capsular stretching of solid organs.

•Parietal pain: innervated on same side and dermatomal level; more distinct and localized. Caused by ischemia, inflammation, or stretching of the parietal peritoneum.

•Referred pain: felt far from the diseased organ; due to shared central pathways for afferent neurons from different locations.

Key knowledge:

Vital signs are particularly important, and must be accurately measured.

Bowel sounds: normally 2-12 gurgles per minute. No bowel sounds over 2 min suggests peritonitis. Hyperactive bowel sounds suggest blood or inflammation within the gut.

Periodic rushes of high-pitched “tinkling” bowel sounds with distention, suggests obstruction.

Rigidity is involuntary spasm of muscles, due to peritoneal irritation.

Voluntary guarding: tensing of the abdominal muscles due to apprehension or discomfort.

Rebound tenderness: increase in pain after quick removal of palpating hand (poor SN & SP).

Carnett’s sign: increased tenderness when the abdominal wall muscles are contracted (95 percent accurate at distinguishing abdominal wall pain from visceral pain).

Murphy’s sign: patient abruptly stops deep inspiration during palpation of the RUQ. Can be useful with suspected cholecystitis.

Psoas sign: with patient on their left side, pain when the right hip is extended (suggests retrocecal appendicitis).

Obturator sign: pain elicited with passive internal rotation of the flexed right thigh (suggests a pelvic appendicitis).

Rovsing’s sign: pain in the RLQ with palpation of the left lower quadrant.

Psoas, obturator, and Rovsing signs have low SN but good SP for acute appendicitis.

Geriatric patients: accuracy of exam findings is decreased in the elderly. Abdominal tenderness may not localize, and peritonitis may not cause rigidity.

Professionalism

1.Present

2.On time

3.Prepared

4.Engaged and participatory

5.Respectful

APPENDIX 2:KEY TEACHING POINTS

Key Teaching Points – Abdominal Pain

1.abdominal pain is common – although frequently benign, it can herald serious pathology

2.triage is important – separate those with possible surgical abdomen and hemodynamic instability

3.history & physical examination are critically important

4.alarm features include:

a.Fever/chills

b.Orthostatic symptoms

c.Alcoholic stools

d.Black stools

e.Bloody stools

f.Change in appearance/character of stools

g.Weight loss or gain

h.Jaundice

i.Pain change with menses

5.differentiate acute from chronic; intervals are arbitrary, but think whether it is an accelerating process, one that has reached a plateau, or one that is long standing but intermittent

6.surgical abdomen – condition with a rapidly worsening prognosis in the absence of surgical intervention (e.g., intraperitoneal hemorrhage, acute appendicitis or viscus perforation)

7.can approach other diagnoses by location: right upper quadrant, epigastric, lower abdominal

8.right upper quadrant pain etiologies include: liver or biliary pathology

9.epigastric pain etiologies include: pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, non-ulcer dyspepsia

10.lower abdominal etiologies include: diarrheal diseases including infection, ileal pathology such as inflammatory bowel disease, left lower quadrant disease including diverticulitis (can also have pain on the right), and pelvic pathology including menstrual disorders, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian disease, endometritis and ectopic pregnancy

11.other causes include functional bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome