ABSTRACT

In response to concerns about future physician shortage, urgent calls have been issued in the USA and Canada to increase medical student positions by 20-30% from current numbers. Yet very little information has been published on how to successfully plan for and manage medical school expansions.

Between 2000 and 2008, the University of Manitoba gradually managed a 53% expansion in Undergraduate Medical Education (UGME) class-size. The latest installment of UGME expansion occurred in 2008-09, amidst concurrent growth in Postgraduate Medical Education. In the same year, a program to evaluate and educate international medical graduates expanded 58% and, a new Physician Assistant Education Program was implemented. To meet the challenge of maintaining quality education for all learners and to appropriately plan for resource development, a systematic inventory of teaching responsibilities and an analysis of the gap between teaching capacity in 2007-08 and future demands were done. Using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, pre-clinical teaching was expressed in instructor-hours while clinical teaching was expressed as learner-weeks in clinical teaching units.

The methodology and the guiding principle that data should be expressed numerically using common units across all departments and programs, aided in unequivocally identifying scarce resources and competing needs. The results, allowing for a Faculty-wide accounting of future commitments, set in motion a teaching-based pro-rating system to allocate funding across departments in a transparent manner. Our methodological approach and experience will be of interest to faculty and administration involved in expansion of health professionals’ education.

INTRODUCTION

A shortage in the physician workforce in the future has been predicted for the United States and Canada.1,2 Urgent calls have been issued in both countries to increase medical student positions by 20-30% from current numbers.2,3 Between 2002-03 and 2011-12, total first-year enrolment at existing medical schools in the United States will likely increase by 2,558 (15.5%) students.4 In Canada, it is recommended that medical school positions should increase from approximately 2,500 to 3,000 as quickly as possible.2

Increasing medical school class size by even 15% increases the need for resources (space, clinical training sites, faculty time, expertise, support staff) and adversely impacts quality of education.5,6 The rapidity with which expansion is expected to occur may be the most challenging aspect of growth for some schools. Only a handful of publications give advice on how best to successfully plan for medical school expansions, and even less discussion has revolved around increasing medical class size amidst simultaneous growth in the training of international medical graduates (IMGs) and other health professionals.7 Yet all of these learners will compete for similar resources during their training and education.

An analysis of challenges and strategies, faced by six institutions in the US that had recently expanded or planned to expand their medical student class size by at least 10%, identified lack of experience among medical educators and administrative leaders as a major challenge.8 This was in part due to the essentially stable enrollment in US and Canadian medical schools over the previous quarter century.8

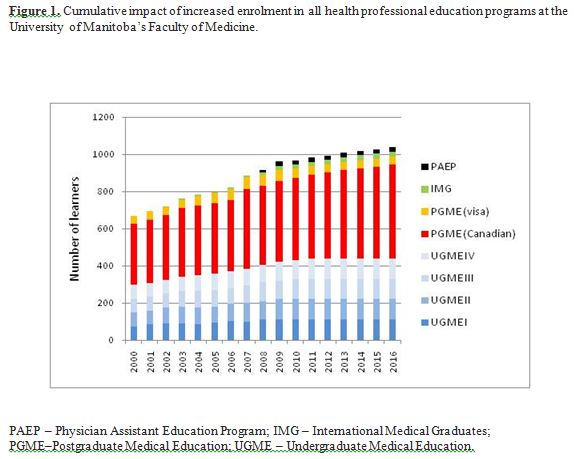

In less than a decade, the Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba, experienced an unprecedented 53% increase in undergraduate medical education (UGME) as incoming medical class size grew from 72 students in 2000-01 to 110 in the fall of 2008-09. An average year-over-year growth of 5.9% was sustained during this period. However, between 2007-08 and 2008-09 alone, the Faculty accommodated almost a 10% growth when incoming class size was increased from 101 students to 110 students. As growth in UGME necessitates a one-on-one growth in linearly-connected postgraduate medical education (PGME) positions, demands on our medical education system will not reach a steady state until the year 2016 (Figure 1). Independent of this anticipated future growth in PGME, in 2008, a unique provincial program was introduced to increase family medicine residencies with a rural/remote (northern) stream by 10 positions.9 Additionally, in 2008 the Faculty of Medicine implemented Canada’s first graduate-level, civilian Physician Assistant Education Program (PAEP). Finally, the IMG program that evaluates and trains IMGs for medical licensure as primary-care physicians in Manitoba and, the nurse-practitioner (NP) program were also expanded, by 58% and 40%, respectively, during the same year. While the IMG program is traditionally overseen by the Faculty of Medicine, the NP program, offered and administered through the Faculty of Nursing, requires resources available within specific clinical sites affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine.

Such multi-level growth (Figure 1) was likely to stress the medical education system of the Province of Manitoba. In order to effectively manage growth, the Faculty adopted a comprehensive and integrated approach to planning curricular and resource needs across all programs. In the summer of 2008, just prior to the start of the academic year 2008-09, we conducted an analysis of the gap between historic teaching capacity and future responsibilities for delivery of curriculum requirements. We considered the year 2007-08 to be representative of our historic teaching commitment and we chose the year 2012-13 to represent our future because enrollment in all UGME classes will have reached 110 that year as will the number in the graduating class. A guiding principle for the gap analysis was that all data summaries and presentations should be expressed in common units across all programs and departments. In this paper we present how we assessed and planned for the impact of growth on the Faculty’s teaching responsibility. Our methodology and experience will be of interest to faculty and administration planning for and managing growth in health professionals’ education.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

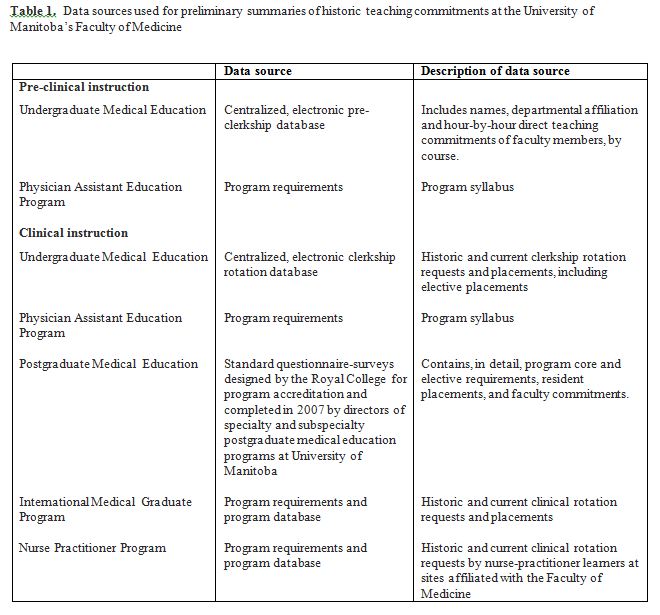

We used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to create preliminary summaries of historic teaching commitments across all departments. The sources of quantitative data were centralized department- or program-specific records and electronic databases (Table 1). Program administrators, directors, and coordinators individually verified or updated these numbers and then provided us with qualitative data, in the form of semi-structured interviews, on program-specific distinctions, needs and concerns, if any, for the future. We made particular note of all areas and units of instruction customarily functioning at maximum capacity, plans toward immediate curriculum reform, development of new teaching units, and changes to program logistics.

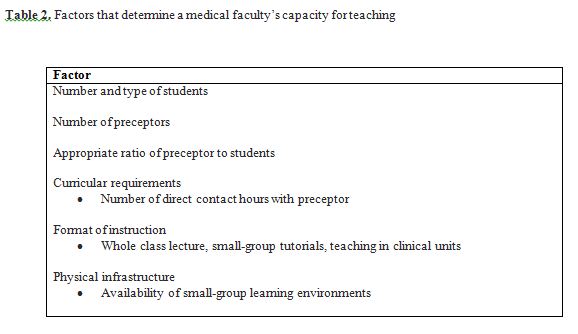

We created a list of critical factors that were thought to determine the Faculty’s teaching capacity. In general, this list includes not only the number and type of learners, the number of preceptors (instructors, tutors), and the number of hours of instruction specified in the program curriculum but also the format of instruction (Table 2). Small-group learning sessions such as tutorials, labs, and clinical skills sessions require more physical and human resources for teaching compared with lecture-sessions. The number of small-group sessions is theoretically determined by the ideal ratio of preceptor to students. An ideal ratio, however, is often altered by limitations of physical infrastructure and availability of human resources.

Analysis of the gap in pre-clinical instruction

We defined teaching commitments in pre-clinical years as the sum total of individual instructors’ direct contact hours with students for all curriculum sessions at all levels of UGME and PAEP, and expressed these commitments in instructor-hours. Instructor-hours were different from student curricular contact hours. For example, a 2-hour small-group tutorial session stipulated in the student curriculum required the Faculty to offer 8 small-group instructional sessions (totaling 16 instructor-hours) for 110 students in all. We presented the gap as the difference between the number of sessions (and hours) offered in the year 2007-08 and the number needed in the year 2012-13.

Analysis of the gap in clinical instruction

Capacity for clinical teaching is a function of clinical teaching units (CTUs). We defined a CTU as a specialty-specific clinical environment such as an inpatient ward or outpatient (ambulatory) clinic with a predetermined maximum limit on the number and type of learners that could be accommodated at any given time. CTUs could be further classified into tertiary-care vs. primary-care; urban vs. rural; teaching hospital vs. community-practice settings. Since the definition and capacity per unit per week of a CTU was site- and discipline-specific, getting input from preceptors and educational coordinators from each department was especially important.

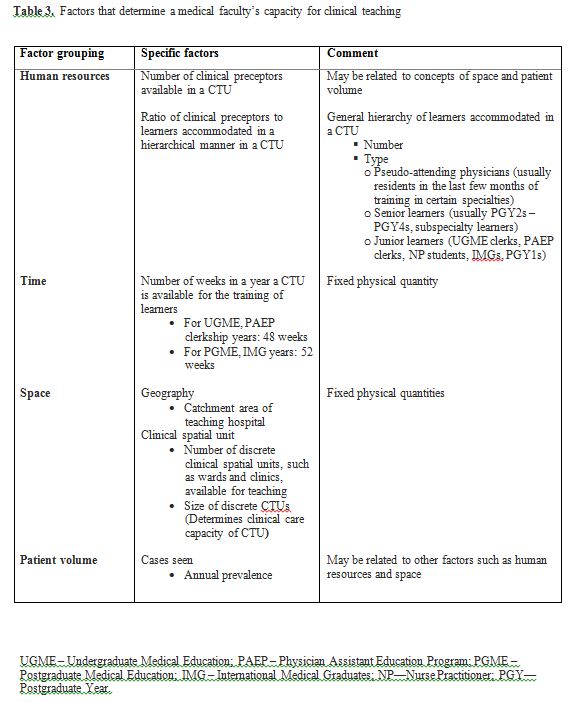

We identified four major groups of factors as limiting our Faculty’s annual capacity for clinical teaching commitments towards learners. These factors include not only human resource issues such as the number of preceptors, but also the physical concepts of time and space (Table 3). Specifically, the academic year is a fixed and pre-defined unit of time, necessitating the accommodation of each successive cohort of learners within this stipulated unit of time. The catchment area of a teaching hospital establishes the number or prevalence of cases seen in a year. While the size of a discrete clinical spatial unit, such as a ward or clinic, determines the clinical care capacity of the CTU, the number and total capacity of all such spatial units available for teaching purposes influence the overall ratio of student to cases. The fourth factor grouping, patient volume, is not unrelated to the other sets of factors but, in some instances, it may be significant enough to be deliberated on its own during planning.

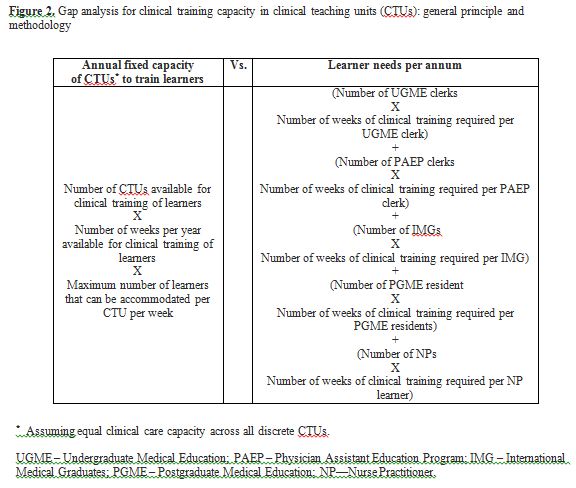

We defined the gap in clinical teaching capacity as the difference between annual fixed capacity of the Faculty to provide clinical training to its learners and the sum total of cumulative clinical training requirements for learners across all programs in the year 2012-13 (Figure 2). We established the annual (maximum) fixed capacity of the Faculty by determining the product of space, time and the capacity per spatial unit per unit of time (assuming equal capacity across all spatial and temporal units). We expressed this fixed capacity in learner-weeks. One learner-week can be described as one week of clinical training offered to one learner. We then calculated cumulative clinical training requirements for learners in each program as the product of the annual number of learners per program and duration, in weeks, of clinical rotation required per learner. The grand total of these products, also expressed in learner-weeks, indicates clinical training requirements for all learners in a given year.

We further divided learner-week requirements into ambulatory care experience vs. inpatient-ward experience; tertiary care setting vs. community practice; rural vs. urban. We examined units that provided sub-specialty experiences for learners to help identify major “bottle-necks” or limiting factors within each department or discipline.

We distributed final Faculty-level and department-specific summaries for validation to heads of departments and to program directors, administrators and coordinators within all programs and departments and other administrative units. Departments of primary appointment of preceptors and instructors, and course coordinators when applicable, were used to create department-specific summaries.

RESULTS

In 2007-08, over 1,500 individual faculty members, including preceptors, tutors, instructors, carried out the teaching responsibilities of the Faculty of Medicine. In addition to university-based teaching sites, learners were placed across 200 urban, rural and remote community-physician practice sites. A total of 9,073 instructor-hours were committed to the 5,058 pre-clinical instructional sessions in UGME; 29,067 clinical learner-weeks were offered collectively to UGME, PGME, IMG and NP programs.

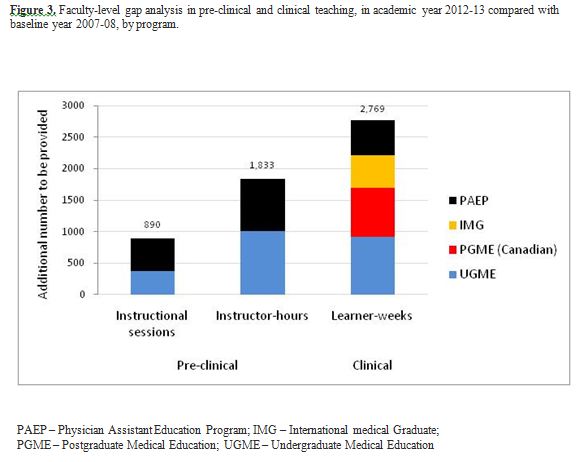

Based on the level of growth in different programs in 2008, the Faculty will gradually be required, over the next five years, to provide up to 10,906 instructor-hours per year for pre-clinical training in UGME and PAEP, and 31,761 learner-weeks per year for clinical training in UGME, PAEP, PGME, IMG programs. Specifically, in 2012-13, the Faculty should be prepared to deliver 890 instructional sessions, 1,833 instructor-hours, and 2,769 clinical learner-weeks in addition to those delivered in the baseline year 2007-08 (Figure 3). Department-specific gap analyses illustrated that Internal Medicine and Family Medicine will absorb the biggest fraction of increased teaching responsibility at the pre-clinical and clinical level, respectively (data not shown).

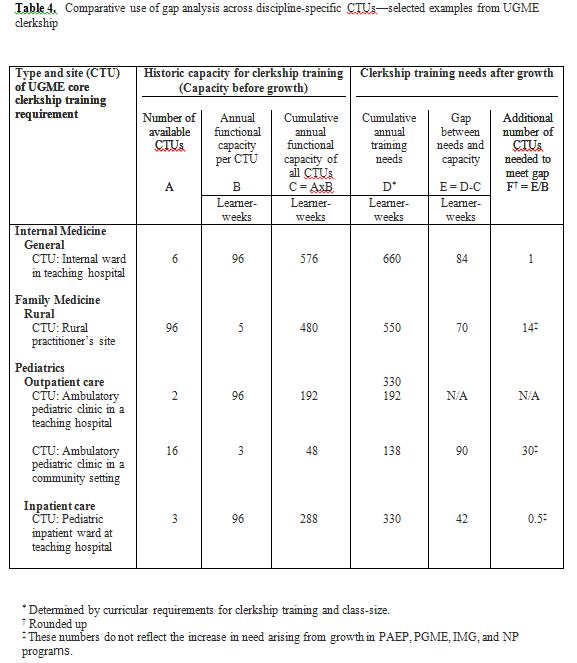

Discipline-based differences in definition and capacity of CTUs notwithstanding, the Faculty was able to identify critical situations and prioritize planning and development. For example, pediatrics ranked first among the departments/disciplines urgently in need of additional community-based, ambulatory- or outpatient-CTUs. We estimated that thirty additional pediatric ambulatory CTUs were required to accommodate growth in UGME alone, assuming that each such CTU will train one UGME clerk for 3 weeks per year (Table 4). Since community-based pediatric CTUs were in demand across all programs (with differing curricular requirements), 96 additional outpatient units will be needed to accommodate growth in UGME, PAEP, PGME, IMG and NP programs, assuming each unit functioned as a CTU for about 3 to 4 weeks a year. Like Pediatrics, Family Medicine too required the development of additional community-based CTUs for all programs. For UGME alone, 14 additional rural practice sites were needed, assuming each site accommodated one UGME clerk for 5 weeks in a year. Internal Medicine, on the other hand, was a representative example of disciplines in need of inpatient-CTUs. At least 1 additional Internal Medicine inpatient ward in a teaching hospital setting was required, at current training capacity, to meet growth at the Faculty level. In general, Pediatrics, Obstetrics & Gynecology, and Family Medicine were most at risk of being overcrowded by the different learner groups. Specific departmental subunits that were identified as potential “bottlenecks” included trauma ward in surgery, outpatient gynecology, pediatric anesthesiology, rural family practice, and northern/remote medicine.

DISCUSSION

The process of identifying the Faculty of Medicine’s historic teaching capacity and future teaching responsibilities has allowed for Faculty-wide accounting of future commitments; identification of scarce resources, competing needs, duplicated efforts; and development of a teaching-based pro-rating system for allocation of funds in a transparent manner. Departmental heads assumed responsibility for translating our gap analysis into human resource planning. A process to review, renew, and update the accounting on an annual basis has also been set in motion.

Benefits of the quantitative, analytical approach

The quantitative approach supported assertions that while some departments were already functioning at maximum capacity (e.g., pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology), a few other departments had room for growth (e.g., psychiatry, general anesthesia). The ability to bring together all departments and communicate, using numbers and common units, the need to rank and prioritize resource development in critical areas, was the ultimate strength of the described methodology. Departments used the projected needs to streamline existing resources, to fast-track plans for developing new CTUs, or to pinpoint the critical juncture in the future at which the development of new CTUs will become inevitable and essential. Quantitative analysis also put to rest the unwarranted fear that implementation of the PAEP will overcrowd our CTUs. The results clearly indicated that there will be only one physician assistant student, on average, in a ward or clinic at any given time. Equally important was the visual impact that within some disciplines/specialties such as family medicine, outpatient gynecology and pediatric emergency care, the NP and UGME programs can potentially compete with each other for clerkship placements.

Lessons learned

The experience of creating an inventory of teaching commitments was made smoother by the availability of centralized course-level or program-level electronic database of teaching commitments. For example, instructors’ departmental affiliations were available in a Microsoft ACCESS database on UGME pre-clinical teaching commitments as were data on curriculum requirements, time and room scheduling, and instructor availability. Such a database allowed for department-specific summaries of our integrated organ/system-based course commitments in an efficient and timely manner. Courses without centralized databases required more labor-intensive and time-consuming accounting methods.

Future directions

One major limitation with the unit ‘learner-week’ is the lack of further refinement to the level of teaching hours and direct contact time between preceptors and students. Our methodology in this phase of the study did not discriminate between the time spent by a learner in clinics with a patient, with or without a physician, and the time spent in other educational activities, namely, didactic hours spent discussing a case, attending academic half-days and using computer simulations and related educational technology. We are planning a subsequent study in which learner-weeks will be systematically categorized into smaller subunits of time. Several smaller, specialized courses (e.g., Advanced Cardiac Life Support), exam refresher courses (e.g., preparation course for Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examinations), extra-curricular opportunities (e.g., early exposure programs) that were not included in the planning and methodology of this paper will also be analyzed in the future study.

To address projected shortages in health professional workforce in the United States and Canada, plans are underway in both countries to establish new, and expand existing, educational programs.1,10 The task of accommodating all such growth can seem daunting. This manuscript documents the systematic methodological approach we used to address and plan for one of the challenges faced in the expansion process, namely the impact of growth on the teaching capacity of our medical faculty. The precise magnitude of our growth and future commitments may not be universally relevant but our methodological approach and experience will be of interest to faculty and administration involved in the expansion of health professionals’ education.

REFERENCES

- Salsberg, E., and Grover, A. Physician workforce shortages: implications and issues for academic health centers and policymakers. Acad Med. 2006; 81(9):782-787.

- Busing N. Managing physician shortages: we are not doing enough. CMAJ. 2007; 176(8):1057-1059.

- AAMC statement on the physician workforce, 2006. Association of American Medical Colleges. Available at: http://www.aamc.org/workforce/workforceposition.pdf. [Accessed December 14, 2009.]

- Medical school expansion plans: results of the 2006 AAMC survey, 2007. Association of American Medical Colleges Center for Workforce Studies. Available at: http://www.aamc.org/workforce/2006medschoolexpansion.pdf. [Accessed December 14, 2009.]

- Hemmer, P.A., Ibrahim, T., and Durning, S.J. The impact of increasing medical school class size on clinical clerkships: A national survey of internal medicine clerkship directors. Acad Med. 2008; 83(5):432-437.

- Bonaminio, G.A., Leapman, S.B., Norcini, J.J., Patel, R.M., and Elnicki, D.M. The educational realities of increasing medical school class size. Acad Med. 2008; 83(10 Suppl):S101-4.

- Bunton, S.A., Sabalis, R.F., Sabharwal, R.K., Candler, C. and Mallon, W.T. Medical school expansion: challenges and strategies. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2008. 115p.

- Bunton, S.A., and Mallon, W.T. Challenges and strategies of medical school expansion. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2008. Available at: http://www.aamc.org/data/aib/aibissues/aibvol8_no2.pdf. [Accessed on December 14, 2009.]

- Northern exposure: new family medicine residency program attracts physicians. Manitoba Medicine. 2008; (1):6.

- Kondro W. Eleven satellite campuses enter orbit of Canadian medical education. CMAJ. 2006; 175(5):461-462.