As I (Associate Dean, Curriculum Development) was sitting in my office pouring through hundreds of e-mails, a faculty member stopped in to express concerns over the students copying material from the tests. “You’ve got to do something about this!” he exclaimed. I sighed, and casually walked to the rear of the classroom to observe what was going on. Sure, enough, several students had their head buried in the test papers, busily typing away on their computers in what looked very much like: Question stem, response option A, response option B, etc. They were not engaged in any of the discussions going on around them – just typing. I came up behind one student who quickly put a piece of paper over his screen. Hmm, I thought, that seem a bit suspicious. As I neared another student, I reminded the class loudly – “Only key points not the full questions.” The faculty member and I walked out again, and I was reminded that I had talked to the class once before. What was I going to do now, he asked?

Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School (Duke-NUS) is a new medical school in Singapore, based on the Duke University Medical School curriculum. One major difference between Duke-NUS and Duke in Durham, North Carolina, is that the first year of basic science instruction is delivered almost exclusively using team-based learning (TBL). 1,2 Our first class began in August 2007. This was the first time that we (faculty and administration) had used TBL in such a comprehensive way; we all had much to learn surrounding the development, implementation, and impact of our decisions on the design and execution of TBL – but that is another story. The story I would like to relate to you in this case presentation is about student note-taking surrounding the test questions from TBL sessions. I will relay what happened, how we handled it and pose several questions for the reviewers and readers to ponder and if possible to respond to.

TBL Model

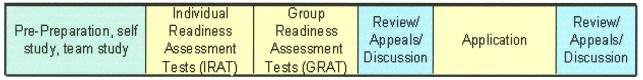

Our implementation of TBL is comprised of the typical components (Figure 1).

- 1)Pre-preparation by students: they study the faculty guided information needed to participate fully in the TBL session.

2)Individual Readiness Assurance Test (IRAT): holding students accountable for their preparation.

3)Group Readiness Assurance Test (GRAT): Students repeat the IRAT as a team.

4)Following GRAT, the faculty briefly review the IRAT/GRAT results and plan their discussion points, while students use this time to discuss the GRAT questions with their group with open resources.

5)Following the closure to the IRAT/GRAT session, we distribute the application questions – where the students need to apply the information they have just discussed.

6)After the application debate/discussions, the teams usually begin to work on their appeals, if any.

Figure 1. Typical Team-Based Learning (TBL) Structure.

The yellow sections (IRAT/GRAT/Application) are where students receive and discuss questions within their teams. The blue sections (Review/Appeals/Discussion) are where students have time to review with teams with open resources after answers are available, write their appeals, and discuss further. It is this time that is often used to make notes about the core concepts discussed during the TBL session.

Writing Test Questions

As anyone who has developed a test knows, it requires significant effort to create quality multiple choice questions (MCQ). It is just as important for TBL session. In addition, since students work with each question quite closely (individually and in group) to analyze and collectively choose answers, ample opportunity exists for students to copy questions. Plus, the learning/study culture for students the world over is to obtain and memorize old test questions. “Is it on the test?” is the universal question. So, having such unfettered access to test questions is a novelty and temptation. When we tried to collect the material at the end of each session, they wanted more time to take notes from the questions to use to study for the summative tests that would follow later in the course.

The concern from the faculty was “Would these notes on the TBL questions be shared with future classes and would that impact on students’ learning?” If future classes knew the questions ahead of time, would they just memorize those answers to get points, and not have done the work to really understand the information? Plus, re-writing questions every year can be an onerous task given the number needed for TBL. For example, the first 6-week course had 13 TBL sessions. Each session had approximately 18 IRAT/GRAT questions, 10 Application questions, for close to 340 questions. In addition, there were 3 summative exams with 80 questions each. That is over 580 questions to re-write for one course.

The challenge and actions taken

As the first block progressed, faculty reported that students were using the extra time available to copy questions rather than participate in group discussion. After much debate among the faculty, we told the class:

- •No copying of test items.

•Use extra time for group discussions surrounding questions for enhanced learning

•If you must take notes about the items – focus on key concepts, not typing what looks like stem and 4 response items.

•We believed copying of the questions verbatim would NOT help them understand the core concepts nor assist them with preparation for future tests.

•And, lastly, we strongly believed that the process each individual and group goes through to study the preparatory material, struggle to answer the questions, and collaborate and learn with their group was part of the power of this learning experience. The learning experience during the group discussions would be greatly diminished if students spent the time copying questions. It also would give rise to the ability of upper classmates to give the questions to the next class, thus robbing them of similar learning opportunities. We acknowledged taking notes about the concepts to assist future study was understandable, but copying the questions verbatim was not appropriate and would be considered a violation of the honor code if seen.

Our mandate to the students was hindered by the “appeals” process within TBL. Teams are permitted to write an appeal on questions if they felt they could make a cogent argument as to why they chose the answer they did. However, in order to write the appeal the students felt they needed to copy down the questions to get the exact syntax and nuances of the response options. This of course, went against our request to not copy questions. We thought we solved that problem by having teams write the question on the back of the appeal form, and turn in the appeal and question together, if necessary.

During the next module, the faculty noted again that several students appeared to be copying questions. Feeling as though our point was not made strong enough, we told the class that we were disappointed and felt that this was possibly an honor code violation. We would set up an honor code panel to discuss the situation and implications. The student leaders of the class provided a compassionate response, suggesting that what might have looked like copying might have been just note-taking. They wanted guidance on how to take notes, as perhaps the message was not clear to everyone. As a class they promised not to share their notes to the new classes, and if anyone did so, they recommended that person should be expelled.

Moved by their plea, the dean felt that the students were genuinely trying to learn the best they knew how, and recommended that a task force be set up instead to look at the student’s response and to better understand the learning environment that created such a need to copy test questions verbatim. We learned some very interesting things at the task force meeting:

- •We found that the student body was hurt and perhaps even wounded that we had attacked their integrity.

•Some students felt that because of our stance on copying, many of them stopped taking any notes during the team activities – for fear they would be viewed as breaking the honor code. (Ironically, there appeared to be no decline in performance even without any note-taking.)

•They also wanted to let us know their intent was honorable and that they were just trying to take notes and learn in the best manner possible.

•Some of the faculty, who had been initially so concerned about the copying, began to see the value of learning the best one can, and became less concerned about the actual copying within the class as long as the student body, as a whole, agreed that they would not share specific content information from the team sessions.

•The students wanted some more explicit guidance on what they could and could not copy and how to communicate with the subsequent classes how to best prepare for the TBL sessions.

The recommendations from the taskforce were that:

- •We wanted to establish a culture in our school that allowed for a trusting relationship between our students and our faculty.

•Students could take notes in any fashion they desired.

•Students were to think of their role as teachers for the subsequent classes, thus just as a faculty member might, they can work with the under- classmates on learning/understanding concepts but not sharing specific questions.

•An honor code statement has been put on all test materials that states that any notes taken from this material are for the individual student only. It would become an honor code violation if the individual should share this test information with another student, or if they knew of anyone else sharing/receiving test information and failed to report it.

•Faculty were encouraged to prepare key summary points from the sessions to ensure students knew what is important to take from the session.

•In addition, faculty were encouraged to make minor modifications to some of the test items each year. (We now recognize this occurs naturally during the discussion phases; the faculty see how questions could be improved and enhanced.)

Our Questions and Concerns

Our subsequent classes and new faculty will no doubt have similar issues, and questions, about our culture of learning. How do we avoid this becoming an issue each year? Or will we have to go through this painful process each year with both faculty and staff to emphasize the values and the core issues?

Does it really matter if questions are passed down from class to class as long as the sessions are well facilitated? Part of the dynamic nature of the TBL process is that students are expected to defend their choices – not just show the answer. If that is done well, and the students use their groups to help them understand why the answers are correct – would it really matter if they had the questions (and answers) ahead of time? We do expect our faculty to make minor changes to items each year and believe the team-based learning process engages the students sufficiently that learning is enhanced – with or without them knowing the “specific” answer.

Do we trust the classes on their honor – or are we just being naïve that students will not share given the intense pressure to score high on all exams and the local cultural beliefs associated with failure? (It should be noted that we had a small, intimate inaugural class of 26 students; they had no upper classmates who could advise them of what works and what did not, what struggles they had experienced and survived; and the cost of “dishonor” is very high in this Asian culture and close-knit small society. Losing the ability to complete their MD degree would be costly here, as there are no other viable options). Does having a reminder about the policy on all test materials make a difference?

Student Response

As a second year medical student, I feel that the issue of trust between students and faculty is of utmost importance. When a school decides to accept a student into its medical training program, the admissions committee should actively seek out students whose past records and reference letters indicate a history of trustworthiness. The practice of medicine requires individuals whom patients and colleagues alike can trust and I feel that this personality trait is present in most medical students. In order to facilitate positive relationships between faculty and students, faculty members need to give the benefit of the doubt to their students in matters of trust until a particular student proves that he or she is not able to be trusted. I think a simple introduction to the course that outlines expectations as well as what is and is not appropriate, perhaps including examples of situations that came up during the inaugural year, would go a long way in acquainting new classes and faculty with the values and core issues at stake during TBL.

If students in the TBL setting agree not to share test material with subsequent classes, faculty members need to trust their word. I do believe that having an honor statement which students must sign on every test serves as a reminder to students of their previous pledges. That being said, I completely understand the view of the faculty in not wanting to let one bad apple ruin the whole bunch. If just one student fails to maintain the trust relationship, the entire incoming class could receive the questions and answers ahead of time and faculty would be stuck in the position of having to rework the course and write a vast amount of new questions.

I participated in a similar TBL course during my first year of medical school and enjoyed the opportunity to discuss problems with my peers in a dynamic setting. The chance to listen to another student’s thought process from start to finish was invaluable and helped me to expand the methods I use to approach problems. I think that coming up with a solution as a group and having to defend that solution is the most beneficial aspect of TBL and could possibly be harmed from students having concrete answers ahead of time. If students know what the answer should be, they may be less likely to explore why other answers are wrong and more inclined to focus only on why the right answer is correct. On the other hand, I do not believe that allowing students to take notes in order to learn in a personally efficient manner necessarily equates with passing the information along to subsequent classes, especially if directly cautioned against. As a medical student, I have never felt compelled, in any course, to give my juniors information about specific test questions nor have I asked members of the class above me for that type of data. Rather, the most frequently discussed questions among students from different classes revolve around which topics are most important to know and which seem to be less so.

If the faculty are truly concerned about students not adhering to the honor policy, then proactive steps, such as faculty preparing key summary points for the students as suggested by the task force in the article, should be taken whenever possible rather than automatically assuming students will cheat if given the opportunity. In conclusion, medical students should be trusted on their honor and should be called upon to uphold their end of the trust relationship; simultaneously, faculty should safeguard their own time and energy invested in the TBL course and its questions by removing any obvious temptation to cheat.

Faculty Response

My first impression was that once you decided on a policy of no copying of the test questions, that any copying would be an honor code violation.

Your recommendations from the task force seem very reasonable. However, I would still be concerned that the summative test at the end of the course work is just too strong an inducement to copy test questions. How much is that test worth? Is the RAT worth much less? If so, there is an incentive for the students to copy. On the other hand, if the RAT is worth an equal or greater part of the course grade as the summative exam at the end, there is less incentive to copy those questions. It seems that the process should be reviewed each year and made a part of the discussions on professionalism that should be held at the start of medical education.

I think that it does matter that questions get passed down from class to class. Of course, if your faculty don’t mind tweaking them, I suppose it would be ok. I’ve used the same or very similar questions for a few years and I don’t think that the students are copying. But, I don’t have a high stakes summative exam. If your goal on the RATs is readiness assurance, they ought to be secure or behind the honor code (as mine are).

Administrator Response

First of all: The Duke/NUS program leadership is to be commended for embarking upon several uncharted waters of starting a medical school with a learning strategy for its curriculum that is novel. We all await their continued publication of what they have done.

One of the great things about starting a ‘new’ school is that the students and faculty can forge a culture that supports active learning, inquiry, and an a code of honor and integrity that endures through successive classes and transitions of faculty. Dr. Cook wonders if they must go through a process every year with students about the protection of questions. I don’t think so, if they instill a value system that begins with a discussion about honor and integrity right from the admissions process; students, as they progress through the four years will take on this value system and insure that subsequent classes maintain the tradition. An Honor Code and signing of an Oath of Honor becomes the shining milestone in the transition from ‘regular person’ to a physician-in-training. It will not even be a question – Can students pass on questions to the next class?

From my and our experience, it is best for our questions in TBL to be fresh for students in a module. Familiarity with detailed objectives is fine, but the most powerful learning occurs with good questions and having to make judgments and choices. It may work that a class of students ‘keeps’ questions for outside class study, but they must value them so highly that they are not transmitted to subsequent classes. It is way too much to ask faculty to craft new and thought-provoking questions every year. Yes, every year they need to come up with new ones, better ones based on student feedback. But, the culture for a curriculum with TBL needs to treasure each module. Student will benefit greatly from both the process of defining a tradition of honor and then practicing it daily.

Respondents

- 1.Student Respondent – Emily Krennerich, MS2, University of Texas Medical School at Houston, Houston, TX

2.Faculty Respondent – Dan Mayer, M.D., Professor of Emergency Medicine, Albany Medical College

3.Dean Respondent – Dean Parmelee, M.D., Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, OH

REFERENCES

- 1.Michealsen, L.K, Knight, A.P and Fink, L.D. Team based learning: A transformative use of the small groups in college teaching, Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, 2004.

2.Michaelsen, L.K, Parmelee, D.X, McMahon, K.K and Levine, R.E. Team-based learning for health professions education: A guide to using small groups for improving learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, 2007.