ABSTRACT

This study posed the following questions: (1) do women and men differ in their overall medical school performance? (2) are there significant differences in the preadmission academic qualifications of female and male medical students? (3) are gender differences in preadmission qualifications a factor in medical school performance? The study included 705 students in four successive classes at the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYCOM). There was no gender difference in undergraduate GPAs, while the mean total MCAT scores of men in all classes were higher than those for women. There was also no significant gender difference between women and men in their cumulative GPAs for the first two years of medical school. Men had higher mean scores on the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination (COMLEX) Level 1, given after the first two years of medical school, but when total MCATs were controlled, there was no gender difference in COMLEX Level 1 performance. MCATs were shown to be correlated with COMLEX Level 1 performance. Clinical performance was determined by scores on clinical subject examinations and the clinically-based COMLEX Level 2 examination. No significant gender differences were seen in these two clinical performance measures. Women outperformed men in evaluations of clinical clerkship performance.

INTRODUCTION

In the last three decades there has been a large increase in the number of women entering the medical profession. In 2004, 50 percent of the entering class of medical students in the United States and 45 percent of the graduating class were women.1 Despite the increase in numbers of women graduating from medical school, their achievement in academic medicine is less than that of men by the conventional standards of academic rank, salary, and publications.2-3 Reasons suggested for the gender gap in academic medicine have included sex differences in career goals, the time commitment incompatible with the raising of children, bias, and a lack of institutional support.2 There have also been recent controversial assertions that women may have less innate science ability.4

A limited number of studies have directly compared medical students with respect to their medical school performance. Men were reported to score better on the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) examination.5 Women performed better than men on clinical clerkships and also on clinical performance examinations.6-7 Osteopathic women medical students outperformed men on clinical clerkships in obstetrics and gynecology.8

A search of both MEDLINE and the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) did not retrieve any published reports comparing the overall performance of women and men at an osteopathic medical school. An important measure of osteopathic medical school performance is performance on the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examinations (COMLEX-USA). The COMLEX-USA Level 1 examination is given after the first two years of medical school, and students are tested on basic science knowledge relevant to medical problems. The COMLEX-USA Level 2-CE (cognitive evaluation) is typically taken in the fourth year and tests knowledge of clinical concepts and principles involved in medical problem-solving.

The present study was designed to answer the following questions: (1) Do women and men differ in their overall medical school performance, including the COMLEX-USA examinations? (2) Are there significant differences in the preadmission academic qualifications of female and male medical students? (3) Are gender differences in preadmission qualifications a factor in medical school performance?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study involved 705 medical students from four successive graduating classes (2002-2005) at the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYCOM). These were traditional students who had completed their course work in four years and had passed the COMLEX-USA Level 1 and Level 2 examinations. The size of each class (2002-2005) was 168, 180, 182, and 175, respectively. The percentage of women in each class was 48%, 46%, 49%, and 50%, respectively. Performance measures included the medical school GPA, clinical subject examinations, clinical evaluations, and the Level 1 and Level 2-CE COMLEX examinations. GPAs and clinical performance data were obtained from institutional databases, and COMLEX-USA examination scores were those reported by the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners to the institution. The average GPA for the first two years of medical school was the cumulative GPA. Clinical subject examinations were given after the clinical clerkships of osteopathic manipulative medicine, family medicine, medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, and surgery. This measure of clinical performance was the mean of the individual subject examinations (clinical examination). The mean of the clerkship evaluations, based on a five point scale, was the clinical evaluation score (clinical evaluation). COMLEX examination scores and MCAT scores were expressed as differences in the mean scores of the genders in each class to preserve the anonymity of privileged school data.

Preadmission data was obtained from the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Application Service. Preadmission academic variables were the cumulative undergraduate GPAs and the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores. Individual subscores were verbal reasoning (verbal MCAT), physical sciences (physical MCAT) and biological sciences (biological MCAT). The total MCAT score was the sum of the three individual subscores.

Medical school performance was measured by comparing the means of the performance measures using the independent-samples t-test. An analysis of covariance using the total MCAT scores as a covariate was performed. Statistical tests were calculated with SPSS statistical software, version 14.0.

RESULTS

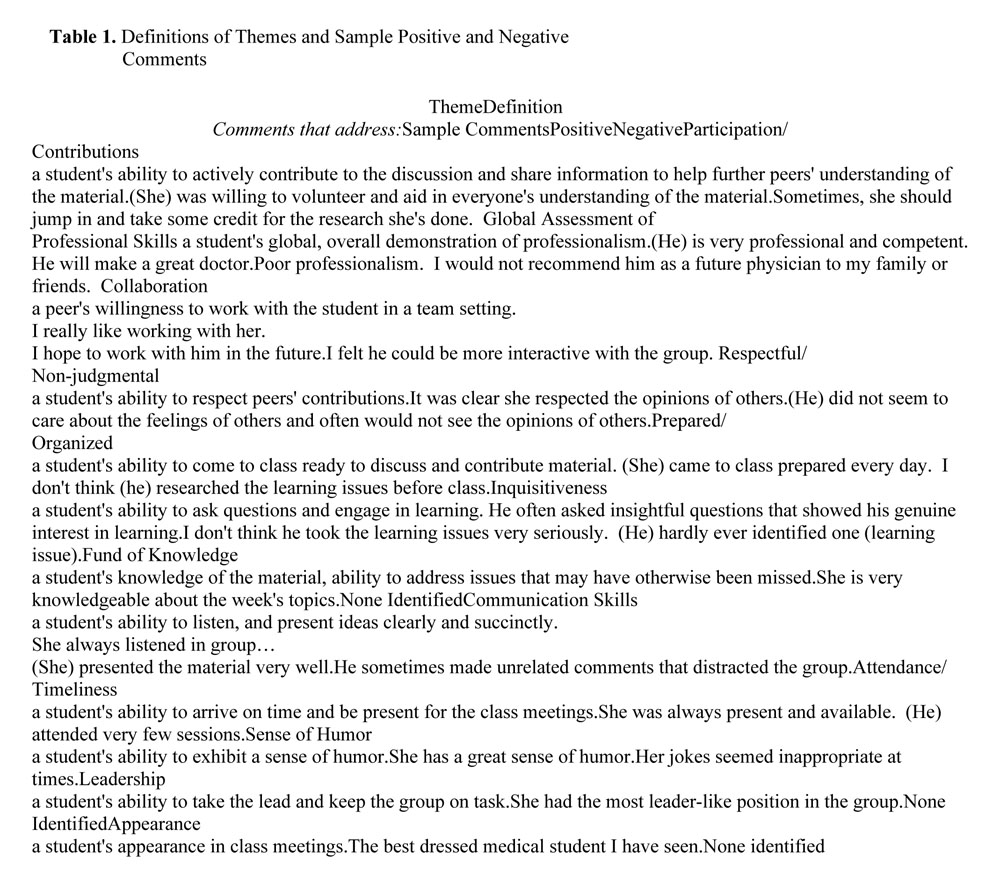

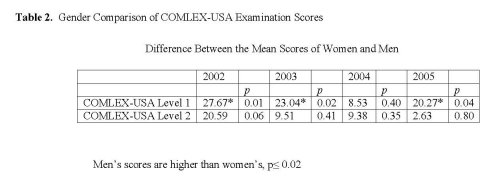

Table 1 shows the cumulative GPAs, clinical evaluation scores, and clinical examination scores of the women and men in each class. There was no difference between women and men in their cumulative GPAs or performance on the clinical subject examinations. Women had higher clinical evaluation scores than men (significant in two classes, p ≤ 0.02). Table 2 shows the gender comparison of COMLEX-USA examination scores. The data is expressed as the difference in the mean scores for women and men. Men in all classes had higher mean COMLEX Level 1 scores than women, and the differences were significant for three of the four classes (p ≤ 0.02). There were no significant gender differences in performance on COMLEX Level 2-CE. The class-based analysis showed that there was a consistent pattern of results across the four classes. There was no discernible gender difference in the performance means in individual classes although the percentage of women increased from the class of 2000 to that of 2005.

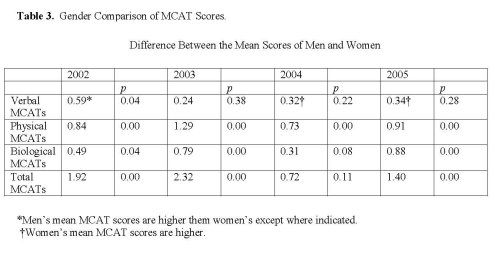

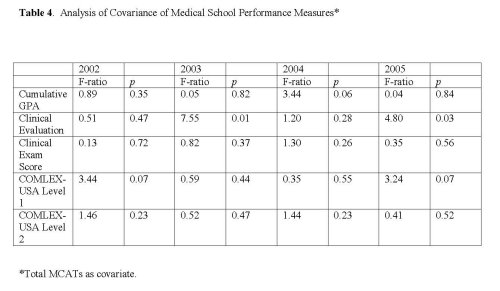

The cumulative undergraduate GPAs of the women and men were not significantly different (data not shown). Analysis of the MCAT scores of the students showed gender differences. Table 3 shows the gender comparison of MCAT scores as the difference between the mean scores of women and men. The total MCAT scores of men in all classes were higher than those of women (difference, 0.72-2.32). This difference was significant in three classes (p ≤ 0.00). Men had higher mean physical MCAT subscores than women in each class (p ≤ 0.00). Biological MCAT subscores were also higher for male students and were significant in three classes (p ≤ 0.04). Women had higher verbal MCAT subscores in two classes, and men had significantly higher verbal MCATs in one class. To examine the effect of MCAT scores on medical school performance, an analysis of covariance was done using the total MCAT scores as a covariate. After controlling for the total MCATs, the COMLEX Level 1 scores of women and men were not significantly different (Table 4). The only gender differences now seen were the higher clinical evaluation scores for women (significant in two of four classes, p ≤ 0.03).

DISCUSSION

The performance of female and male students at NYCOM was equal on the medical school performance measures of cumulative medical school GPA, clinical subject examinations, and COMLEX Level 2-CE examination scores. There was no gender difference in COMLEX Level 1 examination scores when controlling for total MCATs. Women had higher mean clinical clerkship evaluations than men in each class.

While women and men had equivalent undergraduate GPAs, the male students in each of the four classes had higher mean physical and biological science MCATs and total MCAT scores than the women. Physical and biological MCAT scores were previously found to be significant predictor variables for COMLEX level 1 performance at this institution.9 Total MCATs and physical MCATs were reported as predictors for COMLEX level 1 at other osteopathic schools.10-11 Since the COMLEX Level 1 exam is given after the first two years of medical school and focuses on basic science knowledge, the higher total mean COMLEX Level 1 scores for men could be partly due to their higher total MCAT scores. When the total MCATs were controlled, there was no significant difference between women and men with respect to scores on COMLEX Level 1. This finding shows that higher performance in the physical and biological parts of the MCATs is correlated with COMLEX Level 1 performance, and the larger percentage of male students with higher MCATs in each class was the cause of the mean gender difference seen. MCAT scores apparently had little effect on performance on the clinically-based COMLEX Level 2-CE examination.

The performance of women in the clinical years was found to be equal to that of men, and higher than men in the case of clinical clerkship evaluations. The ratings for the clerkship evaluations are somewhat subjective. The rating sheets for attitude / professionalism and clinical skills include items such as cooperation, patient communication, and receptivity to feedback. These are areas in which women may excel. Women have been reported to have greater abilities to actively listen and create better relationships with patients than men.7 It can be postulated that the women’s higher clinical evaluation grades found in this study may reflect their better abilities in the areas of cooperation, patient communication, interviewing, and counseling.

This is one of only a few studies that have reported gender comparisons of both preclinical and clinical performance of medical students at an osteopathic or allopathic medical school. The results show that women graduating from this medical school in recent years are the academic equals of their male classmates. It is hoped that in the future, some of these women will choose careers in academic medicine and help to redress the gender inequalities.

REFERENCES

- Magrane, D., and Jolly, P. The changing representation of men and women in academic medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges. Analysis In Brief. July 2005. Available at http://www.aamc.org/data/aib/start.htm Accessed May 22, 2007.

- Hamel, M.B., Ingelfinger, J.R., Phimister, E., and Solomon, C.G. Women in academic medicine – progress and challenges. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006; 355(3):311-312.

- Wright, A.L., Schwindt, L.A., Bassford, T.L., Reyna, V.F., Shisslak, C.M., St. Germain, P.A., and Reed, K.L. Gender differences in academic advancement: patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one U.S. college of medicine. Academic Medicine. 2003; 78:500-508.

- Handelsman, J., Cantor, N., Carnes, M., Denton, D., Fine, E., Grosz, B., Hinshaw, V., Marrett, C., Rosser, S., Shalala, D., and Sheridan, J. More women in science. Science. 2005; 309:1190-1191.

- Ramsbottom-Lucier, M., Johnson, M.M.S., and Elam, C.L. Age and gender differences in students’ preadmission qualifications and medical school performance. Academic Medicine. 1995; 70:236-239.

- Haist, S.A., Wilson, J.F., Elam, C.L., Blue, A.V., and Fosson, S.E. The effect of gender and age on medical school performance: an important interaction. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2000; 5:197-205.

- Haist, S.A., Witzke, D.B., Quinlivan, S., Murphy-Spencer, A., and Wilson, J.F. Clinical skills as demonstrated by a comprehensive clinical performance examination: who performs better – men or women? Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2003; 8:189-199.

- Krueger, P.M. Do women students outperform men in obstetrics and gynecology? Academic Medicine. 1998; 73:101-102.

- Dixon, D. Relationship between variables of preadmission, medical school performance, and COMLEX-USA Levels 1 and 2 performance. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2004; 104:332-336.

- Meoli, F.G., Wallace, W.S., Kaiser-Smith, J., and Shen, L. Relationship of osteopathic medical licensure examinations with undergraduate admission measures and predictive value of identifying future performance in osteopathic principles and practice/osteopathic manipulative medicine courses and rotations. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2002; 102:615-620.

- Cope, M.K., Baker, H.H., Fisk, R., Gorby, J.N., and Foster, R.W. Prediction of student performance on the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination Level 1 based on admission data and course performance. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2001; 101:84-90.