ABSTRACT

In this manuscript we have demonstrated the effective use of pamphlet design by students taking the physiology course at a chiropractic school. The activity helped students to hone their skills by working in groups, develop creativity and apply physiological concepts to real life situations. A rubric was adopted to grade the pamphlets. At the end of the course, the students had the opportunity to present their work during a lab session and communicate with colleagues on their projects. The students benefited immensely from this unique learning experience and encouraging feedback was received on this learning activity.

INTRODUCTION

In observing healthcare institutions, clinics use brochures, leaflets or pamphlets as helpful resources to educate patients. In recent years, more emphasis has been given in designing pamphlets, including the implementation of cognitive psychology to augment the effectiveness of their use.1 These educational tools are designed and distributed for a number of reasons, including tools to address general health education material, educating patients on the safety and use of a pharmaceutical agent, addressing important health issues, when advertising and recruiting teaching faculty and/or for research purposes.2-7 Moreover, at Northwestern Health Sciences University, physiology students enrolled in the chiropractic program are required to develop a brochure or pamphlet that amalgamates physiology course work with chiropractic medicine. The learning activity constitutes about 10% of the student’s final grade. As a summative assessment, the designing pamphlet assignment motivates students to learn, work in a team and apply basic science principles to both clinical sciences and common clinical presentations. The learning objectives for designing a pamphlet were as follows:

•Students will understand and use online programs to design a pamphlet

•Students will perform retrieval of references from online resources with assistance from the university library

•Students will develop and demonstrate the ability to work in a group

•Students will appreciate their communication and presentation skills

•Students will apply principles of physiology to a clinical or a real life scenario

Details of the Pamphlet/Brochure as a Summative Assessment:

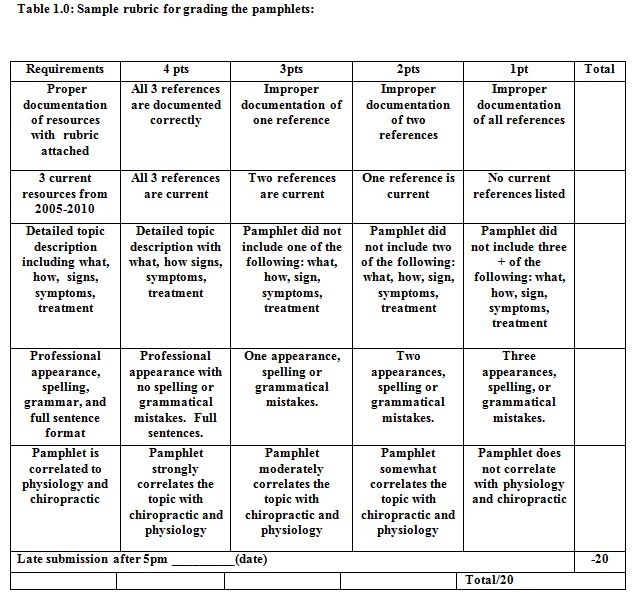

Based on an outlined assessment rubric (see Table 1.0), a total of 25 points was allocated for the research and design of the pamphlet. These pamphlets would cover information relative to a physiology topic of study correlated to and pertinent to patient education. Students worked in groups of two with the working partner assigned from the same lab section. Although strongly discouraged and pending individual circumstances, a student had the option to work independently. Students were to refrain from choosing a partner from another lab section to avoid unnecessary confusion and logistic work for instructors. In the introductory lab session, students were made aware that pamphlets would be graded based on the rubric in Table 1.0. Before starting the project, students were given the following guidelines:

- All topics are approved by the professor before a given deadline and are submitted on index cards with title and names of the group members. The index cards are provided by the instructor (different colored cards were chosen for different lab sections) and 5 points were awarded for timely submission.

- All pamphlets are due by a given date to receive 20 points based on the rubric. Points are deducted for late submission.

- Pamphlets are accepted as a single page, bifold or in a trifold format.

- The font size should be appropriate with no double spacing.

- All pamphlets are properly documented with at least 3 sources (2005 or later) and written with proper grammar and spelling.

- Any student caught plagiarizing will be subjected to academic review.

- Students who decide to use this pamphlet as a resource for patient education are suggested to have copyright approval for any material, pictures or diagrams they have used in their brochures.

- The students are required to initial and sign for record that they understood the aforementioned guidelines.

Sharing Knowledge

Towards the end of the term, one of the lab sessions was dedicated to student presentations. Prior to this presentation, students distributed copies of their pamphlet, both to their instructor and to students in their lab section. Ten (10) points were allocated solely to their presentation, independent from the developmental phase of the pamphlet. The following aspects were considered when evaluating the students.

•Students made a 5 minute presentation to discuss content of the pamphlet and share acquired knowledge with lab members

•Each presentation was followed by a 5 minute question and answer session

•Students were assessed on the clarity of their presentation, team work and their ability to answer questions on their topic

•An independent faculty member could also be invited to evaluate the students

DISCUSSION

Student perspective on this learning activity:

The clinical physiology pamphlet exercised a multitude of dimensions: application of basic physiology to common clinical presentations, integration from other course work, effective patient communication, and critical thinking.

Applying our physiology course work in this particular assignment was an effective way to summarize important course-related details that may otherwise have been forgotten. At times, it is easy to get lost in the plethora of material presented in the classroom. If not provided the opportunity to exercise and apply the principles presented, students may fail to fully grasp and understand the course’s fundamental objectives. Because of the activity, basic concepts of which may be pertinent for chiropractors, such as the role of basic sciences in the development of an accurate diagnosis and other future clinical applications are subsequently lost and underappreciated. This project aimed to substantiate the learning objectives.

Additionally, this assignment provided students with the opportunity to apply basic physiology principles to common clinical presentations: diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypertension, to name a few. The assignment encouraged students to think critically about the role of human physiology in these commonly diagnosed conditions. As a result, group members challenged one another on their knowledge regarding the topic, researched the topic, incorporated course work from other areas, for example histology, and radiology, and even went as far as to discuss how we as future chiropractors could care for patients with similar presentations. This integrative experience contributed to a thorough understanding of the fundamental principles, their clinical applications, and available treatment options for the chosen topic.

Furthermore, students quickly learned to appreciate the importance of effective patient communication. One challenge of particular relevance involved taking a wealth of information pertaining to the chosen topic and summarizing it into a clear and concise document that encompassed the topic’s clinically relevant information and in such a way a patient would understand. Students become accustomed to using medical vernacular throughout their chiropractic training and get away from using common, everyday language. While working on this assignment, students quickly learned to appreciate the difficulty of this task as well as the preparation and practice required to convey information about a particular subject. The use of plain language in brochures has been previously highlighted in the literature.8

Finally, this assignment capitalized on a number of different learning styles: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. Visual learners prospered while gathering and presenting relevant diagrams to explain the underlying physiological principles and their relation to the medical condition. Auditory learners benefited greatly during group discussions and as spectators during the in-lab presentations, and the kinesthetic learners excelled while organizing the information and constructing the pamphlet. This interactive assessment provided students with the opportunity to utilize and apply their own unique learning style to accomplish the outlined objectives and gain insight into the role basic science education has in the clinical aspects of their chiropractic education.

Teacher perspective on this learning activity:

Educators in the medical discipline have shown concern on the basic science instruction model and whether it can meet the future challenges in medical education.9 Basic sciences are a strong component in medical education and innovative assessments to test and increase student knowledge should be periodically added to a course such as medical physiology.10,11 Introducing activities such as designing a brochure, pamphlet or poster within a medical curriculum can make basic science subjects more attractive and fascinating to learn. To reinforce, introducing brochure or pamphlet design in early part of the medical curriculum can bridge gap between clinical and basic science knowledge.

Students learn to apply basic science concepts to clinical scenarios that can spark their interest to investigate about patho-physiological concepts.

Henceforth, in early part of the chiropractic curriculum this activity gives students the opportunity to enhance their critical thinking and simultaneously hone their pamphlet designing skills. More importantly, the activity was designed to familiarize students to latest research articles and introduce them to the concept of evidence based medicine. The students in the course practiced to retrieve peer reviewed references via the library or internet. The intention was to make students appreciate the clinical applications in physiology. As chiropractors or any clinician, this exercise will be useful to design pamphlets for patient education in their future clinics and could have tremendous impact on their practice.12 As shown previously, brochures complement strong physician-patient interaction.13

To conclude, the students took great pride in their brochures and developed a mutual understanding and team spirit to complete the project. Taken together, since the activity was being conducted in the basic sciences department it was important to make students realize that basic sciences are an important core of the chiropractic curriculum. To reiterate, sound understanding of basic science principles is required to excel in a chiropractic or medical program and subsequently as a clinician.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Verena Van Fleet, Associate Prof. of Basic Sciences at Northwestern Health Sciences University and India Broyles, Director of the Medical Education Leadership Program at University of New England for their advice and suggestions towards this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Whittingham, J.R., Ruiter, R.A., Castermans, D., Huibert, A., Kok, G. Designing effective health education materials: experimental pre-testing of a theory-based brochure to increase knowledge. Health Educ Res. 2008; 23: 414-426.

- Hodgson, C.S., Francisco, S., Baillie, S. Using a brochure to recruit faculty to teach. Acad Med. 2001; 76: 577.

- Kools, M., Ruiter, R.A., van de Wiel, M.W., Kok, G. Testing the usability of access structures in a health education brochure. Br J Health Psychol.2007; 12: 525-541.

- Lautrette, A., Darmon, M., Megarbane, B.,et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356: 469-478.

- Naito, M., Nakayama, T., Ojima, T., et al. Creating a brochure to promote understanding of epidemiologic research. J Epidemiol. 2004; 14: 174-176.

- van Zuuren, F.J., Grypdonck, M., Crevits, E., Vande Walle, C., Defloor, T., et al. The effect of an information brochure on patients undergoing gastrointestinal endoscopy: a randomized controlled study. JVIR. 2006; 64: 173-182.

- Wang, T.C., Kyriacou, D.N., Wolf, M.S. Effects of an intervention brochure on emergency department patients’ safe alcohol use and knowledge. J Emerg Med. 2008; (epub ahead of print).

- Nagel, K.L., Wizowski, L., Duckworth, J., Cassano, J., Hahn, S.A., Neal, M. Using plain language skills to create an educational brochure about sperm banking for adolescent and young adult males with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008; 25: 220-226.

- Crown, V. A study to examine whether the basic sciences are appropriately organized to meet the future needs of medical education. Acad Med.1991; 66: 226-31.

- Beaty, H.N. Changes in medical education should not ignore the basic sciences. Acad Med. 1990; 65: 675-676.

- Norman, G. Role of basic sciences in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1997; 2: 93-94.

- Chesanow, N. A brochure that really sells your practice. Med Econ. 1998; 75: 59-61.

- Fosse, K., Kurtz, E., Khanna, V., Camacho, F.T., Balkrishnan, R., Feldman, S. A practice brochure: complement to, not supplement for, good physician-patient interaction. Arch Dermatol. 2007; 143: 1447.